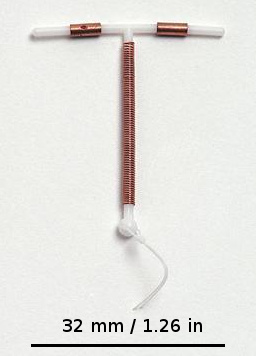

含铜避孕器

| 含铜避孕器 | |

|---|---|

含铜避孕器(Paragard T 380A)的照片 | |

| 背景 | |

| 生育控制种类 | 子宫内 |

| 初次使用日期 | 1970年[1] |

| 失效率比率 (第一年) | |

| 完美使用 | 0.6% |

| 一般使用 | 0.8% |

| 用法 | |

| 持续期间 | 5–12年以上[1] |

| 可逆性 | 快速[1] |

| 注意事项 | 定期检查避孕器的位置,若更年期时尚未移除含铜避孕器,需尽早移除 |

| 医师诊断 | 每年一次 |

| 优点及缺点 | |

| 是否可以防止性传播疾病 | 否 |

| 周期 | 月经量会比较多,可能会比较痛[2] |

| 好处 | 不需日常例行性的服药,若要紧急避孕,需在性行为后五天内置入 |

| 风险 | 置入的前20天有小幅骨盆腔发炎的风险[2] ,有子宫穿孔的风险,但非常罕见 |

含铜避孕器(英语:copper intrauterine device,也称铜制子宫内避孕器、子宫内避孕圈(intrauterine coil)、铜圈(copper coil)或是非荷尔蒙型子宫内避孕器(non-hormonal IUD)),是一种长效可逆避孕方式,也是目前最有效的避孕方法之一。[3][2]它也可在未采取防护措施的性行为后的5天内作为紧急避孕用途。[2]该装置置入子宫内,有效期可长达12年,具体取决于装置中的铜含量。[2][1]无论个体的年龄或先前是否曾怀孕,都可使用此装置进行避孕,且可在阴道分娩、剖腹产或手术流产后立即置入。[4][5]当装置移除后,生育能力可迅速恢复。[1]

使用此类装置常见的副作用有经血过多和经痛加剧。罕见的案例有避孕器可能会脱落或穿透子宫壁。[2][1]

含铜避孕器最初于20世纪初在德国开发,但在1970年代才于医学领域广泛使用。[1]此装置已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中。[6][7]

医疗用途

[编辑]含铜避孕器是一种长效且可逆的避孕方式,也是目前最有效的避孕方法之一。[3][8]不同装置的框架类型和铜含量会影响其有效性。[9]

含铜避孕器一经置入便立即生效,移除或是置入位置不正时则无避孕作用。[10]置入含铜避孕器第一年的有效性(失败率0.8%)与输卵管结扎术(失败率0.5%)相当。[11][12][10]不同此类装置的失败率在使用一年后介于0.1%到2.2%之间。铜表面积为380平方毫米(mm²)的T形装置失败率最低。型号为TCu 380A (Paragard) 的装置一年失败率为0.8%,累积12年的失败率为2.2%。[9]铜表面积较小的模型在超过12年的使用中,有较高的失败率。型号为为TCu 220A的12年失败率为5.8%。型号为GyneFix的无框架装置每年失败率低于1%。[13]于2008年所进行,对现有T形铜制子宫内避孕器的回顾建议,TCu 380A和TCu 280S应作为铜制子宫内避孕器的首选,因为这两型号的失败率最低,且寿命最长。[9]而在全球。有效率较低的旧型子宫内避孕器模型均已停产。[14]

虽然监管机构对此类装置所批准最长使用期限仅为12年,但有些的可能有效期可长达20年。[15]

含铜避孕器不含激素,因此不会干扰使用者的月经周期时间,也不会阻止排卵。[3]

紧急避孕

[编辑]含铜避孕器于1976年首次被发现可用于紧急避孕(EC)。[16]这种装置是最有效的紧急避孕方法,比口服激素紧急避孕药(包括美服培酮、醋酸乌利司他及左炔诺孕酮)更为有效。[17][已过时][18]且不受使用者体重影响。[10]使用含铜避孕器进行紧急避孕者的怀孕率为0.09%。它可用于无保护性行为后5天内进行的紧急避孕,在此5天内的效果不会降低。[19]使用此种避孕器进行紧急避孕的另一个优点是置入后可成为10-12年的避孕方法。[19]

移除与生育能力恢复

[编辑]移除含铜避孕器应由合格的医护人员执行。研究显示在移除后,个体的生育能力会迅速恢复到之前水平。[20]

副作用与并发症

[编辑]并发症

[编辑]使用此避孕装置最常发生的并发症是装置脱落、子宫穿孔和感染。停止使用后出现的不孕和使用期间哺乳困难与装置无关。[10][20]

装置脱落率在第1年到第10年之间,可能会在2.2%到11.4%的使用者中发生。TCu 380A的脱落率可能低于其他型号,而无框架装置的脱落率与有框架的型号相似。[21][22]在产后立即或早期放置,或者流产后放置,会有较高的脱落可能。[23][24]当装置在胎盘娩出后不到10分钟内放置,或在剖腹产后插入时,脱落的可能性较小。[15]个体出现不寻常的阴道分泌物、痉挛或疼痛、经期之间出血、性行为后点状出血、性交疼痛或装置线绳消失或延长,都可能是装置脱落的征兆。[20]装置脱落后立即失去避孕效果,与刻意移除的结果相似。一项研究估计若在脱落发生后重新插入装置,一年后约有3分之1的再次脱落风险。[25]磁振造影 (MRI) 可能会导致含铜避孕器器移位,因此建议在MRI之前及之后均需检查装置的位置。[26]

装置穿透子宫壁通常发生在放置时,但也可能在使用期间自行发生。穿孔率的估计值从每1,000次置入有1.1次,到每3,000次置入有1次不等。[1][10]在进行母乳哺育的个体使用此装置的,穿孔的几率可能会略高。[27]

完全穿孔的含铜避孕器会导致发炎,通常需经手术移除。若装置周围与人体组织形成致密粘连。可通过子宫镜或手术的方式移除。[1][15]

当装置置入后,会在21天内带来短暂的骨盆腔发炎 (PID) 风险,但这几乎是在置入时,个体有未诊断出的淋病或披衣菌感染的情况下发生。这种情况发生的几率低于1/100。超过此时段,使用含铜避孕器不会增加骨盆腔发炎的风险。[15][28][10][29][20]如果分娩没有绒毛羊膜炎等感染复杂因素,产后置入此装置并不会增加感染风险。[15]

副作用

[编辑]使用含铜避孕器最常见的副作用是经血增加和经痛,两者通常在置入3-6个月后缓解。较不常见的是可能会发生经期之间出血,尤其是在使用最初的3-6个月内。[10][20][30]在不同的研究中对经血增加量有所不同,有的低至20%,或高至55%,但没有证据显示个体的铁蛋白、血红素或血细胞比容发生相应变化。[1][10]

经血过多和经痛通常可使用非类固醇抗发炎药 (NSAID,如萘普生、布洛芬和甲芬那酸) 治疗。[31][15]

避孕失效

[编辑]

使用子宫内避孕器而发生子宫外孕的绝对风险,由于整体怀孕率大幅降低,会低于不避孕的。然而当使用此装置却发生怀孕时,出现子宫外孕的百分比更高,从3%到6%,增加2到6倍。此情况相当于含铜避孕器使用者每1,000人年发生0.2 - 0.4次子宫外孕的绝对发生率,相对的,未避孕人群中每1,000人年会发生3次子宫外孕。[32][10][1]

如果在使用子宫内避孕器的情况下让怀孕持续,会增加并发症的风险,包括早产、绒毛羊膜炎和流产。如果把装置移除,这些风险会降低,特别是出血和流产的风险。前述的流产接近一般人群的水平,具体取决于研究的对象。[32][1][10]

含铜避孕器的总体失败率很低,主要取决于装置中的铜表面积。在连续使用12年后,TCu 380A装置的累积怀孕率为1.7%。[1]TCu 380A比MLCu375、MLCu350、TCu220和TCu200更有效。TCu 380S比TCu 380A更有效。[33]无框架装置的失败率与传统有框架的装置相似。[13]

禁忌症

[编辑]含铜避孕器用于哺乳期和未曾怀孕过的女性中被认为是安全及有效。在世界卫生组织 (WHO) 发布的《避孕药具使用医疗资格标准(Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use)》中,列有含铜避孕器的第3类禁忌症(风险通常大于益处)和第4类禁忌症(不可接受的健康风险)。第3类禁忌症有未经治疗的艾滋病、近期和反复暴露于淋病或披衣菌且未接受充分治疗、良性妊娠滋养细胞疾病和卵巢癌。除怀孕和活动性生殖道感染(例如骨盆结核、性传染病、子宫内膜炎)外,第4类禁忌症还包括恶性妊娠滋养细胞疾病、异常子宫出血、活动性子宫颈癌、肝豆状核变性(威尔森氏症)和活动性子宫内膜癌。只要经过治疗,艾滋病感染本身并非禁忌症。 含铜避孕器与抗反转录病毒药物之间并无已知的药物相互作用。[15][34][35]

装置描述

[编辑]

类型

[编辑]目前全球生产有许多不同类型的含铜避孕器,但各国的供应情况有所不同。

作用机制

[编辑]

含铜避孕器的主要作用机制是阻止受精。[10][20][36][37][38]装置上的铜会引起局部发炎反应,有杀精子作用,导致子宫内膜不适合受孕。[10][20][15][36]

进入子宫腔和子宫颈的精子会被局部吞噬细胞消耗,并直接被铜离子和溶酶体内容物杀死。铜离子的存在会扰乱精子的运动能力,导致无法受精。[1]

铜可能会干扰胚胎植入(但非主要作用机制),[10][39]特别是在用于紧急避孕时。[40][41]如果发生胚胎植入,没证据显示铜会影响后续妊娠的发育或导致胚胎失败。[10][36]含铜避孕器因而被认为是一种真正的避孕装置,而非堕胎装置。[10][20]

使用情况

[编辑]子宫内避孕器是使用最广泛的可逆避孕法。全球截至2020年有1.61亿人使用子宫内避孕器(包括不含激素以及含激素的)。截至2020年,子宫内避孕器在14个国家(主要位于中亚和东亚)中是最受欢迎的避孕方法。[42]

截至2006年,欧洲的含铜避孕器的普及率从英国、德国和奥地利的5%以下到丹麦和波罗的海国家的10%以上不等。[43]

历史

[编辑]最早在20世纪初即有子宫内避孕器前身的相关报导。但它们与高发的生殖道感染,特别是淋病有关,因此没受广泛采用。[44]

完全包含在子宫内的子宫内避孕器,是由Richard Richter首度在1909年一份德国出版物中描述。[44]

德裔美国医学家恩斯特·格雷芬贝格于1929年发表一份关于丝线制成的子宫内避孕器(称为格雷芬贝格环)的报告,最初附有一小段银线,以便在X光下显影,然后完全用银线包裹,之后改用含铜合金线。此装置在英国和英联邦国家广泛使用,而在美国和欧洲,由于人们认为存在感染、癌症和无效的风险,并不鼓励使用。[45][44]

日本医师大田典礼于1934年开发一种格拉芬贝格环的变体,但受到当时执政者阻挠。他在第二次世界大战后重返子宫内避孕器的开发。到1950年代末,日本使用32种不同的框架形状装置,且经证明此类装置与子宫内膜癌之间并无关联(这曾是人们对子宫内金属具有发炎特性而产生的担忧)。大田典礼的装置在日本一直使用到1980年代。[46][44]

第一个塑胶装置由一曾在奥匈帝国军队服务,名为拉扎尔·马古利斯的军医开发,并于1959年首次试用。马古利斯在1962年对装置进行修改,增加串珠尾部。[47][48][44]

商品名为Lippes Loop的产品是一种稍小的塑胶材质装置,带有单丝尾部,于1962年推出,并比马古利斯装置更受欢迎。[49]

在1960年代和70年代,不锈钢线被引入作为铜镍锌合金的替代品,[44]随后因制造成本低廉而在中国受到广泛使用。因为其失败率很高(每年高达10%)中国政府在1993年禁止生产钢制子宫内避孕器。[14][50]

美国妇产科医师霍华德·塔图姆 在1967年构思塑胶T形子宫内避孕器,[51]但因有高达约18%失败率而不实用。[44][52]不久后,智利医师海梅·齐珀发现镍银合金由于其铜含量有杀精子作用,而在前述塑胶T形装置上添加铜套,将失败率降低到约1%。[44][49][53]人们发现含有铜的装置可在不影响有效性的情况下制成更小的尺寸,而能减少疼痛和出血等副作用。[14]由于T形装置与子宫形状更相似,会有较低的脱落率。[54]

霍华德·塔图姆开发许多不同型号的含铜避孕器。他在型号为TCu 220 C的装置使用铜环而非铜丝,可防止金属损失过速而延长装置寿命。第二代铜T形子宫内避孕器也在1970年代推出。这些装置具有更高的铜表面积,并且首次持续达到超过99%的有效率。[14]塔图姆开发的最终型号TCu 380A于1984年获得美国食品药物管理局(FDA)批准,且是目前最受推荐的装置。[9][55]

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Goodwin TM, Montoro MN, Muderspach L, Paulson R, Roy S. Management of Common Problems in Obstetrics and Gynecology 5. John Wiley & Sons. 2010: 494–496. ISBN 978-1-4443-9034-6. (原始内容存档于2017-11-05).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 World Health Organization. Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR , 编. WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. 2009: 370–2. ISBN 9789241547659. hdl:10665/44053

.

.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 2012, 366 (21): 1998–2007 [2019-08-18]. PMID 22621627. S2CID 16812353. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110855

. (原始内容存档于2020-08-17).

. (原始内容存档于2020-08-17).

- ^ Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Hubacher D, Stuart G, Van Vliet HA. Immediate postpartum insertion of intrauterine device for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. June 2015, 2015 (6): CD003036. PMC 10777269

. PMID 26115018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003036.pub3. 已忽略未知参数

. PMID 26115018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003036.pub3. 已忽略未知参数|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 69. British Medical Association. 2015: 557–559. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Schäfer-Korting M. Drug Delivery. Springer Science & Business Media. 2010: 290. ISBN 978-3-642-00477-3. (原始内容存档于2017-11-05).

- ^ Hofmeyr GJ, Singata M, Lawrie TA. Copper containing intra-uterine devices versus depot progestogens for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. June 2010, 2010 (6): CD007043. PMC 8981912

. PMID 20556773. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007043.pub2. 已忽略未知参数

. PMID 20556773. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007043.pub2. 已忽略未知参数|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Kulier R, O'Brien PA, Helmerhorst FM, Usher-Patel M, D'Arcangues C. Copper containing, framed intra-uterine devices for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. October 2007, (4): CD005347. PMID 17943851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005347.PUB3.

- ^ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Implants and Intrauterine Devices: Practice Bulletin #186. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2024 [2025-01-28] (英语).

- ^ Contraceptive Use in the United States. The Guttmacher Institute. 2012 [2013-10-04]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-04).

- ^ Bartz D, Greenberg JA. Sterilization in the United States. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008, 1 (1): 23–32. PMC 2492586

. PMID 18701927.

. PMID 18701927.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 O'Brien PA, Marfleet C. Frameless versus classical intrauterine device for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2005, (1): CD003282. PMID 15674904. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003282.pub2.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 IUDs--an update (PDF). Population Reports. Series B, Intrauterine Devices (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Population Information Program). December 1995, (6): 1–35 [2006-07-06]. PMID 8724322. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-10-29).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Bradshaw KD, Corton MM, Halvorson LM, Hoffman BL, Schaffer M, Schorge JO (编). Williams Gynecology. McGraw-Hill's AccessMedicine 3rd. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Education LLC. 2016. ISBN 978-0-07-184909-8.

- ^ Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Advances in Planned Parenthood. 1976, 11 (1): 24–29. PMID 976578.

- ^ Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Cheng L , 编. Interventions for emergency contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. April 2008, (2): CD001324. PMID 18425871. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001324.pub3.

- ^ Ramanadhan S, Goldstuck N, Henderson JT, Che Y, Cleland K, Dodge LE, Edelman A. Progestin intrauterine devices versus copper intrauterine devices for emergency contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. February 2023, 2023 (2): CD013744. PMC 9969955

. PMID 36847591. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013744.pub2. 已忽略未知参数

. PMID 36847591. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013744.pub2. 已忽略未知参数|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ 19.0 19.1 Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Human Reproduction. July 2012, 27 (7): 1994–2000. PMC 3619968

. PMID 22570193. doi:10.1093/humrep/des140.

. PMID 22570193. doi:10.1093/humrep/des140.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Dean G, Schwarz EB. Intrauterine contraceptives (IUCs). Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W J, Kowal D, Policar MS (编). Contraceptive technology 20th revised. New York: Ardent Media. 2011: 147–191 (150). ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. 温哥华格式错误 (帮助)

- ^ O'Brien PA, Marfleet C. Frameless versus classical intrauterine device for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2005, (1): CD003282. PMID 15674904. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003282.pub2. 已忽略未知参数

|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ Kaneshiro B, Aeby T. Long-term safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of the intrauterine Copper T-380A contraceptive device. International Journal of Women's Health. August 2010, 2: 211–220. PMC 2971735

. PMID 21072313. doi:10.2147/ijwh.s6914

. PMID 21072313. doi:10.2147/ijwh.s6914  .

.

- ^ Okusanya BO, Oduwole O, Effa EE. Immediate postabortal insertion of intrauterine devices. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. July 2014, 2014 (7): CD001777. PMC 7079711

. PMID 25101364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001777.pub4. 已忽略未知参数

. PMID 25101364. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001777.pub4. 已忽略未知参数|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ Averbach SH, Ermias Y, Jeng G, Curtis KM, Whiteman MK, Berry-Bibee E, Jamieson DJ, Marchbanks PA, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC. Expulsion of intrauterine devices after postpartum placement by timing of placement, delivery type, and intrauterine device type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. August 2020, 223 (2): 177–188. PMC 7395881

. PMID 32142826. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.045.

. PMID 32142826. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.045.

- ^ Bahamondes L, Díaz J, Marchi NM, Petta CA, Cristofoletti ML, Gomez G. Performance of copper intrauterine devices when inserted after an expulsion. Human Reproduction. November 1995, 10 (11): 2917–2918. PMID 8747044. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135819.

- ^ Berger-Kulemann V, Einspieler H, Hachemian N, Prayer D, Trattnig S, Weber M, Ba-Ssalamah A. Magnetic field interactions of copper-containing intrauterine devices in 3.0-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging: in vivo study. Korean Journal of Radiology. 2013, 14 (3): 416–422. PMC 3655294

. PMID 23690707. doi:10.3348/kjr.2013.14.3.416.

. PMID 23690707. doi:10.3348/kjr.2013.14.3.416.

- ^ Berry-Bibee EN, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jamieson DJ, Curtis KM. The safety of intrauterine devices in breastfeeding women: a systematic review. Contraception. December 2016, 94 (6): 725–738. PMC 11283814

. PMID 27421765. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.006.

. PMID 27421765. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.006.

- ^ Mohllajee AP, Curtis KM, Peterson HB. Does insertion and use of an intrauterine device increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with sexually transmitted infection? A systematic review. Contraception. February 2006, 73 (2): 145–153 [2020-09-30]. PMID 16413845. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.007. (原始内容存档于February 6, 2020).

- ^ Infection Prevention Practices for IUD Insertion and Removal. (原始内容存档于2010-02-01). By the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Retrieved on 2010-02-14

- ^ Costescu D, Chawla R, Hughes R, Teal S, Merz M. Discontinuation rates of intrauterine contraception due to unfavourable bleeding: a systematic review. BMC Women's Health. March 2022, 22 (1): 82. PMC 8939098

. PMID 35313863. doi:10.1186/s12905-022-01657-6

. PMID 35313863. doi:10.1186/s12905-022-01657-6  .

.

- ^ Christelle K, Norhayati MN, Jaafar SH. Interventions to prevent or treat heavy menstrual bleeding or pain associated with intrauterine-device use. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. August 2022, 2022 (8): CD006034. PMC 9413853

. PMID 36017945. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006034.pub3. 已忽略未知参数

. PMID 36017945. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006034.pub3. 已忽略未知参数|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ 32.0 32.1 Molino GO, Santos AC, Dias MM, Pereira AG, Pimenta ND, Silva PH. Retained versus removed copper intrauterine device during pregnancy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. January 2025. PMID 39868878. doi:10.1111/aogs.15061

.

.

- ^ Kulier R, O'Brien PA, Helmerhorst FM, Usher-Patel M, D'Arcangues C. Copper containing, framed intra-uterine devices for contraception. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. October 2007, (4): CD005347. PMID 17943851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005347.pub3. 已忽略未知参数

|collaboration=(帮助) - ^ Jatlaoui TC, Riley HE, Curtis KM. The safety of intrauterine devices among young women: a systematic review. Contraception. January 2017, 95 (1): 17–39. PMC 6511984

. PMID 27771475. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.006.

. PMID 27771475. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.006.

- ^ World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use 5th. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2015. ISBN 9789241549158. hdl:10665/181468

.

.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB. Copper-T intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine system: biological bases of their mechanism of action. Contraception. June 2007, 75 (6 Suppl): S16–S30. PMID 17531610. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.020. p. S28:

- ^ Speroff L, Darney PD. Intrauterine contraception. A clinical guide for contraception 5th. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: 239–280. ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6. p. 246:

- ^ Jensen JT, Mishell Jr DR. Family planning: contraception, sterilization, and pregnancy termination. Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Katz VL (编). Comprehensive gynecology. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. 2012: 215–272. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1. p. 259:

- ^ ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Intrauterine devices and intrauterine systems. Human Reproduction Update. May–June 2008, 14 (3): 197–208. PMID 18400840. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn003

. p. 199:

. p. 199:

- ^ Speroff L, Darney PD. Special uses of oral contraception: emergency contraception, the progestin-only minipill. A clinical guide for contraception 5th. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: 153–166. ISBN 978-1-60831-610-6. p. 157:

Emergency postcoital contraception

Other methods

Another method of emergency contraception is the insertion of a copper IUD, anytime during the preovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle and up to 5 days after ovulation. The failure rate (in a small number of studies) is very low, 0.1%.34,35 This method definitely prevents implantation, but it is not suitable for women who are not candidates for intrauterine contraception, e.g., multiple sexual partners or a rape victim. The use of a copper IUD for emergency contraception is expensive, but not if it is retained as an ongoing method of contraception. - ^ Trussell J, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception. Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W J, Kowal D, Policar MS (编). Contraceptive technology 20th revised. New York: Ardent Media. 2011: 113–145 (121). ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734.

Mechanism of action

温哥华格式错误 (帮助)

Copper-releasing IUCs

When used as a regular or emergency method of contraception, copper-releasing IUCs act primarily to prevent fertilization. Emergency insertion of a copper IUC is significantly more effective than the use of ECPs, reducing the risk of pregnancy following unprotected intercourse by more than 99%.2,3 This very high level of effectiveness implies that emergency insertion of a copper IUC must prevent some pregnancies after fertilization.

Pregnancy begins with implantation according to medical authorities such as the US FDA, the National Institutes of Health79 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).80 - ^ World Family Planning 2022 (PDF) (报告). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2022 [2025-02-01]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2025-01-30).

- ^ Sonfield A. Popularity Disparity: Attitudes About the IUD in Europe and the United States. The Guttmacher Institute. 2012. (原始内容存档于2010-03-07).

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 44.6 44.7 Margulies L. History of intrauterine devices. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. May 1975, 51 (5): 662–667. PMC 1749527

. PMID 1093589.

. PMID 1093589.

- ^ Baldauf P, Tönnes R, Simon S, David M. A Report on the Hysteroscopic Removal of a Gräfenberg Ring After Almost Fifty Years in Utero. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. November 2014, 74 (11): 1023–1025. PMC 4245252

. PMID 25484377. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1383130.

. PMID 25484377. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1383130.

- ^ Muvs - Tenrei Ota (1900-1985). muvs.org. [2025-02-02] (英语).

- ^ Coils. Museum of Contraception and Abortion. [2025-02-01].

- ^ Sivin I, Stern J. Long-acting, more effective copper T IUDs: a summary of U.S. experience, 1970-75. Studies in Family Planning. October 1979, 10 (10): 263–281. JSTOR 1965507. PMID 516121. doi:10.2307/1965507.

- ^ 49.0 49.1 Lynch CM. History of the IUD. Contraception Online. Baylor College of Medicine. [2006-07-09]. (原始内容存档于2006-01-27).

- ^ Kaufman J. The cost of IUD failure in China. Studies in Family Planning. May–Jun 1993, 24 (3): 194–196. JSTOR 2939234. PMID 8351700. doi:10.2307/2939234.

- ^ Advancing long-acting reversible contraception. Population Briefs. April 2013, 19 (1).

- ^ Corbett M. A History: The IUD. Reproductive Health Access Project. March 20, 2024 [2025-02-01] (美国英语).

- ^ Van Kets HE. Capdevila CC, Cortit LI, Creatsas G , 编. Importance of intrauterine contraception. Contraception Today, Proceedings of the 4th Congress of the European Society of Contraception. The Parthenon Publishing Group: 112–116. 1997 [2006-07-09]. (原始内容存档于2006-08-10). (Has pictures of many IUD designs, both historic and modern.)

- ^ Salem R. New Attention to the IUD: Expanding Women's Contraceptive Options To Meet Their Needs. Popul Rep B. February 2006, (7). (原始内容存档于2007-10-13).

- ^ Corbett M, Bautista B. A History: The IUD. Reproductive Health Access Project. 2024-03-20 [2025-03-11].