用户:Eri0n0ire/沙盒

Taxonomy

[编辑]Sedum was first formally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, with 15 species.[1] Of the genera encompassed by the Crassulaceae family, Sedum is the most species rich, the most morphologically diverse and most complex taxonomically. Historically, it was placed in the subfamily Sedoideae, of which it was the type genus. Of the three modern subfamilies of the Crassulaceae, based on molecular phylogenetics, Sedum is placed in the subfamily Sempervivoideae. Although the genus has been greatly reduced, from about 600[2] to 420–470 species,[3] by forming up to 32 segregate genera,[4] it still constitutes a third of the family and is polyphyletic.[5]

Sedum species are found in four of six major crown clades within subfamily Sempervivoideae of Crassulaceae and are allocated to tribes, as follows:[6]

| Clade | Tribe |

|---|---|

| Hylotelephium | Telephieae |

| Rhodiola | Umbiliceae |

| Sempervivum | Semperviveae |

| Aeonium | Aeonieae |

| Acre | Sedeae |

| Leucosedum | |

| Note

Clades containing Sedum, shown in blue | |

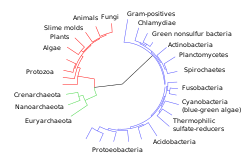

In addition, at least nine other distinct genera appear to be nested within Sedum. However, the number of species found outside of the first two clades (Tribe Sedeae) are only a small fraction of the whole genus. Therefore the current circumscription, which is somewhat artificial and catch-all must be considered unstable.[5] The relationships between the tribes of Sempervivoideae is shown in the cladogram.

| Cladogram of Sempervivoideae tribes[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are now thought to be approximately 55 European species in the genus. Sedum demonstrates a wide variation in chromosome numbers, and polyploidy is common. Chromosome number is considered an important taxonomic feature.[7]

Earlier authors placed a number of Sedum species outside of these clades, such as S. spurium, S. stellatum and S. kamtschaticum (Telephium clade),[8] that has been segregated into Phedimus (tribe Umbiliceae).[6][9][10][11] Given the substantial taxonomic challenges presented by this highly polyphyletic genus, a number of radical solutions have been proposed for what is described as the "Sedum problem", all of which would require a substantial number of new combinations within Sempervivoideae. Nikulin and colleagues (2016) have recommended that, given the monophyly of Aeonieae and Semperviveae, species of Sedum outside of the tribe Sedeae (all in subgenus Gormania) be removed from the genus and reallocated. However, this does not resolve the problem of other genera embedded within Sedum, in Sedeae.[5] In the largest published phylogenetic study (2020), the authors propose placing all taxa within Sedeae in genus Sedum, and transferring all other Sedum species in the remaining Sempervivoideae clades to other genera. This expanded Sedum s.l. would comprise about 755 species.[12]

Subdivision

[编辑]Linnaeus originally described 15 species, characterised by pentamerous flowers, dividing them into two groups; Planifolia and Teretifolia, based on leaf morphology, with 15 species, and hence bears his name as the botanical authority (L.).[13] By 1828, de Candolle recognized 88 species in six informal groups.[14] Various attempts have been made to subdivide this large genus, in addition to segregating separate genera, including creation of informal groups, sections, series and subgenera. For an extensive history of subfamily Sedoideae, see Ohba 1978.

Gray (1821) divided the 13 species known in Britain at that time into five sections; Rhodiola, Telephium, Sedum, (unnamed) and Aizoon.[15] In 1921, Praeger established ten sections; Rhodiola, Pseudorhodiola, Giraldiina, Telephium, Aizoon, Mexicana, Seda Genuina, Sempervivoides, Epeteium and Telmissa.[16] This was later revised in what is the best known system, that of Berger (1930), who defined 22 subdivisions, which he called Reihe (sections or series).[17] Berger's sections were:

- Rhodiola

- Pseudorhodiola

- Telephium

- Sedastrum

- Hasseanthus

- Lenophyllopsis

- Populisedum

- Graptopetalum

- Monanthella

- Perrierosedum

- Pachysedum

- Dendrosedum

- Fruticisedum

- Leptosedum

- Afrosedum

- Aizoon

- Seda genuina

- Prometheum

- Cyprosedum

- Epeteium

- Sedella

- Telmissa

A number of these, he further subdivided.[17] In contrast, Fröderströmm (1935) adopted a much broader circumscription of the genus, accepting only Sedum and Pseudosedum within the Sedoideae, dividing the former into 9 sections.[18] Although this was followed by numerous other systems, the most widely accepted infrageneric classification following Berger, was by Ohba (1978).[19] Prior to this, most species in Sedoideae were placed in genus Sedum.[9] Of these systems, it was observed "No really satisfactory basis for the division of the family into genera has yet been proposed".[20]

Some other authors have added other series, and combined some of the series into groups, such as sections.[21] In particular, Sedum section Sedum is divided into series (see Clades) [5][22] More recently, two subgenera have been recognised, Gormania and Sedum.[5]

- Gormania: (Britton) Clausen. 110 species from Sempervivum, Aeonium and Leucosedum clades. Europe and North America.

- Sedum: 320 species from Acre clade. Temperate and subtropical zones of Northern hemisphere (Asia and the Americas).[23]

Subgenus Sedum has been considered as three geographically distinct, but equal sized sections:[23]

- S. sect. Sedum ca. 120 spp. native to Europe, Asia Minor and N. Africa, ranging from N. Africa to central Scandinavia and from Iceland to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus and Iran.

- S. sect. Americana Frod.

- S. sect. Asiatica Frod.

S. sect. Sedum includes 54 species native to Europe, which Berger classified into 27 series.[23]

Clades

[编辑]Species and series include[24][25][26][8][6][5][4][27]

Subgenus Gormania

[编辑]Semperviveae

[编辑]Of about 80 Eurasian species, series Rupestria forms a distinct monophyletic group of about ten taxa, which some authors have considered a separate genus, Petrosedum.[29][30][31] It was series 20 in Berger's classification. Native to Europe it has escaped cultivation and become naturalized in North America.[32]

Aeonieae (N Africa)

[编辑]Embedded within series Monanthoidea are three Macaronesian segregate genera, Aichryson, Monanthes and Aeonium.[6]

Sedeae - Leucosedum (Europe/Mediterranean/Near East/Central Asia)

[编辑]- S. series Aithales (Med)

- S. pallidum M.Bieb.

- S. series Alba (Med)

- S. series Alsinefolia All. (Med)

- S. series Atrata (Med)

- S. series Brevifolia (Med)

- S. series Cepaea (Med)

- S. commixtum Moran & Hutchison

- S. series Convertifolia (Med)

- S. series Dasyphylla (Med)

- S. series Glauco-rubens (Med)

- S. series Gracile (Med)

- S. series Hirsuta (Med)

- S. hirsutum All.

In the Levant, one species of this succulent (S. microcarpum) covers the stony ground like a carpet where the soil is shallow, growing no higher than 5–10 cm. At first, the fleshy leaves are a light green, but as the season progresses, the fleshy leaves turn red.

Europe/Mediterranean/Near East/Central Asia

[编辑]- Sedum series Inconspicua (Med)

- S. ince 't Hart & Alpinar

- S. lydium Boiss.

- S. microcarpum (Sm.) Schönland

- S. series Monregalense (Med)

- S. moranii R.T.Clausen

- S. series Nana (Med)

- S. series Pedicellata (Med)

- S. sedoides (Jacquem. ex Decne.) Pau

- S. series Steico (Med)

- S. series Subrosea (Med)

- S. series Subulata (Med)

- S. series Telmissa (Med)

- S. series Tenella (Med)

- Med = Mediterranean distribution

Embedded within the Leucosedum clade are the following genera: Rosularia, Prometheum, Sedella and Dudleya.[6] Rosularia is paraphyletic, and some Sedum species, such as S. sempervivoides Fischer ex M. Bieberstein are assigned by some authors to Rosularia, as R. sempervivoides (Fischer ex M. Bieberstein) Boriss.[34]

Subgenus Sedum

[编辑]Sedeae - Acre (Asia/Europe/Macaronesia/N. America)

[编辑]- S. series Alpestria Berger

- S. alpestre Vill. (Europe)

- S. series Acria[12]

- S. acre L. (Europe)

- S. bourgaei Hemsl. (Mexico)

- S. bulbiferum Makino (Asia)

- S. burito Moran (Mexico)

- S. cockerellii Britton (N. America)

- S. dendroideum Moc. & Sessé ex DC. (Mexico)

- S. farinosum Lowe (Macaronesia)

- S. furfuraceum Moran (N. America)

- S. fusiforme Lowe (Macaronesia)

- S. hakonense Makino (Asia)

- S. hemsleanum Rose (N. America)

- S. japonicum Siebold ex Miq. (Asia)

- S. laconicum Boiss. & Heldr. (Mediterranean)

- S. lineare Thunb. (syn. S. subtile) (Asia)

- S. litoreum Guss. (Europe)

- S. series Macaronesica (Macaronesia)

- S. makinoi Maxim. (Asia)

- S. meyeri-johannis Engl. (Africa)

- S. mexicanum Britton (Asia)

- S. morrisonense Hayata (Asia)

- S. multicaule Wall. ex Lindl. (Asia)

- S. multiceps Coss. & Durieu (Europe, N Africa, S America)

- S. nudum Aiton (Macaronesia)

- S. oaxacanum Rose (N. America)

- S. obcordatum R.T. Clausen (N. America)

- S. oreades (Decne.) Raym.-Hamet (Asia)

- S. oryzifolium Makino (Asia)

- S. section Pachysedum (N. America)

- S. plumbizincicola X.H.Guo & S.B.Zhou ex L.H.Wu (China)

- S. polytrichoides Hemsl. (Asia)

- S. reptans R.T.Clausen (Mexico)

- S. rubrotinctum R.T. Clausen (Americas, Australasia)

- S. sarmentosum Bunge (Asia)

- S. sexangulare L. (Europe)

- S. ternatum Michx. (N. America)

- S. tosaense Makino (Asia)

- S. triactina A.Berger (Asia)

- S. trullipetalum Hook.f. & Thomson (Asia)

- S. urvillei DC. (Mediterranean)

- S. yabeanum Makino (Asia)

- S. zentaro-tashiroi Makino (Asia)

Embedded within the Acre clade are the following genera: Villadia, Lenophyllum, Graptopetalum, Thompsonella, Echeveria and Pachyphytum.[6] The species within Acre, can be broadly grouped into two subclades, American/European and Asian.[35][8]

List of selected species

[编辑]- Sedum acre L. – wall-pepper, goldmoss sedum, goldmoss stonecrop, biting stonecrop

- Sedum albomarginatum Clausen – Feather River stonecrop

- Sedum album L. – white stonecrop

- Sedum alfredii

- Sedum anglicum – English stonecrop

- Sedum brevifolium

- Sedum burrito – baby burro's-tail

- Sedum caeruleum

- Sedum cauticola

- Sedum clavatum

- Sedum cyprium

- Sedum dasyphyllum L. – thick-leaved stonecrop

- Sedum debile S.Watson – orpine stonecrop, weakstem stonecrop

- Sedum dendroideum Moc. & Sessé ex A.DC. – tree stonecrop

- Sedum divergens S.Watson – spreading stonecrop

- Sedum eastwoodiae (Britt.) Berger – Red Mountain stonecrop

- Sedum erythrostictum syn. Hylotelephium erythrostictum

- Sedum glaucophyllum Clausen – cliff stonecrop

- Sedum hispanicum L. – Spanish stonecrop

- Sedum lampusae (Kotschy) Boiss.

- Sedum lanceolatum Torr. – lance-leaf stonecrop, lanceleaf stonecrop, spearleaf stonecrop

- Sedum laxum (Britt.) Berger – roseflower stonecrop

- Sedum lineare – needle stonecrop

- Sedum mexicanum Britt. – Mexican stonecrop

- Sedum microstachyum (Kotschy) Boiss. – small-spiked stonecrop

- Sedum moranii Clausen – Rogue River stonecrop

- Sedum morganianum – donkey tail, burro tail

- Sedum multiceps – pygmy Joshua tree, dwarf Joshua tree

- Sedum niveum A.Davids. – Davidson's stonecrop

- Sedum nussbaumerianum Bitter, syn. Sedum adolphi – golden sedum

- Sedum oaxacanum Rose

- Sedum oblanceolatum Clausen – oblongleaf stonecrop

- Sedum obtusatum Gray – sierra stonecrop

- Sedum obtusatum ssp. paradisum Denton – paradise stonecrop

- Sedum ochroleucum Chaix – European stonecrop

- Sedum oreganum Nutt. – Oregon stonecrop

- Sedum oregonense (S.Watson) M.E.Peck – cream stonecrop

- Sedum palmeri S.Watson – Palmer's stonecrop

- Sedum perezdelarosae Jimeno-Sevilla

- Sedum porphyreum Kotschy – purple stonecrop

- Sedum pulchellum Michx. – widow's-cross

- Sedum radiatum S.Watson – Coast Range stonecrop

- Sedum rubrotinctum – pork and beans, Christmas cheer, jellybeans

- Sedum rupestre L. – reflexed stonecrop, blue stonecrop, Jenny's stonecrop, prick-madam

- Sedum sarmentosum Bunge – stringy stonecrop

- Sedum sediforme (Jacq.) Pau pale stonecrop

- Sedum sexangulare – tasteless stonecrop

- Sedum sieboldii – Siebold's stonecrop

- Sedum smallii, syn. Diamorpha smallii – Small's stonecrop

- Sedum spathulifolium Hook.f. – Broadleaf stonecrop, Colorado stonecrop

- Sedum spurium – Caucasian stonecrop, dragon's blood sedum, two-row stonecrop

- Sedum stenopetalum Pursh – wormleaf stonecrop, yellow stonecrop

- Sedum telephium L.

- Sedum ternatum Michx. – woodland stonecrop

- Sedum takesimense

- Sedum telephium

- Sedum villosum – hairy stonecrop, purple stonecrop

- Sedum weinbergii

————————————————————————————————————————————————

Previous phylogenetic studies found that Nomocharis is nested within Lilium and is a sister taxon to L. nepalense. These studies contained N. saluenensis (I˙kinci et al. 2006; Nishikawa et al.1999, 2001), N. aperta, and sect. Eunomocharis species (Gao et al. 2012a). In our analysis, we obtained similar results (Fig. 1).

2013年Du等人和2019年Kim等人先后用不同类型的DNA数据,以不同的采样规模分析了百合属物种的演化历史,并将结果与Comber早在1949年发表的传统分类系统相对比。Du等人以中国分布的百合属为采样重点,使用了98种的细胞核糖体转录间隔区数据进行分析,其结果大体支持Comber对喇叭花组基于鳞茎颜色的分类,并认为南川百合和湖北百合应从卷瓣组归入喇叭花组。

Kim等人的分析采用了28种百合属的质体基因组及片段数据,

支持、南川百合与亲缘较近,

发现本属主要分化为两大支系,一支为东亚及欧洲分布,另一支为横断山脉及北美洲分布。在组的层面,根茎组和喇叭花组均为多系群,而轮叶组的祖先则可能演化自卷瓣组[36]。该文章并未进行任何分类学处理和修订,但不排除未来出现采样更全面的系统演化研究以及分类修订的可能性。

————————————————————————————————————————————————

| 进化生物学 |

|---|

|

群体遗传学(population genetics)又称族群遗传学、种群遗传学,是研究在自然选择、性选择、遗传漂变、突变以及基因流动这五种进化动力的影响下,等位基因的分布和改变。通俗而言,群体遗传学就是在种群水平上进行研究的遗传学分支,探究适应、物种形成、种群结构等自然现象的格局、规律和成因。

群体遗传学理论在现代进化综论中至关重要。本学科在传统上是高度数学化的学科,例如自1980年代起便成为核心计算方法的溯祖理论,而现代的群体遗传学包括理论的、实验室的和实地的工作。得出的群体遗传模型既可用于特定概念的证明或证伪,也可对DNA序列进行统计推断。

该学科的主要创始者包括休厄尔·赖特、约翰·伯顿·桑德森·霍尔丹和罗纳德·费雪等,也是定量遗传学领域的理论奠基者。

进化动力

[编辑]突变

[编辑]是多样性的来源。在群体遗传学主要区分为中性突变、有益突变和有害突变。

可逆的突变可以作如下表示:[37]

其中p和q代表等位基因的的频率,μ和ν是突变率,t是时间。

平衡状态是:

自然选择

[编辑]自然选择发生于不同的基因型有不同适应度时:[38]

其中f(x)为x的频率,是x的相对适应度。即是整个种群的平均适应度。适应度也可用选择系数(selection coefficient)表示为。值得注意的是适应度不一定是一个常数,而可能是基因频率的函数,这种情况称为频率依赖选择(frequency-dependent selection)。负为频率依赖选择,也就是频率低的基因较适应的情况,是维持基因多样性的一个重要机制。另一个可以维持基因多样性的情况是超显性,即异型合子的适应度最高。

基因流

[编辑]当个体在不同种群间移动时,称为迁徙(migration)或基因流(geneflow)。

在两个面积类似的栖地之间(两岛屿模型)的基因流可用如下式子表示:

其中和分别代表某个等位基因两个栖地中的频率,m是迁徙率。

当一个栖地远大于另一个时(陆地—岛屿模型),则用如下式子:

C和I分别代表陆地和岛屿的基因频率。如果没有别的进化动力,最终岛屿的基因频率会和陆地相同。

性选择

[编辑]各种非随机交配会造成性选择。

x是基因型频率,是雌i对雄j的偏好,1代表AA,2代表Aa。

遗传漂变

[编辑]当种群大小有限时,会因为单纯的几率造成基因频率的改变。可以用二项分布描述基因频率从一个值变为另一个值的几率。当种群大小是N时,等位基因有2N个,经一个世代后,种群中会有j个A基因的几率是:[39]

因为0<q<1,种群大小(N)越小时,这个几率越高。

除了用二项分布配合马可夫链来计算,漂变也可以用一维布朗运动的扩散方程来描述。[40]

因为模型都经过一定的简化,方程式中的N并不完全对应到真实世界的种群大小,而被称为有效种群大小。[41]

应用

[编辑]推断群体结构

[编辑]对于双倍体、有性繁殖的物种,最简单的群体结构检测方法是计算其种群中基因型的频率是否符合哈代-温伯格平衡律(简称哈温平衡)的预测,即该物种种群中单个位点的基因型是否符合不受上述五种进化动力影响时,理论上会呈现的频率(没有天择、没有性择、没有突变、种群无限大、没有遗传漂变、没有基因流)。

将该位点的两个等位基因A和a的频率分别标记为 p 和 q,哈温平衡下三种基因型的频率应分别为:[42]

当进化动力存在时,会造成基因型频率偏离哈温平衡,包括等位基因频率的改变和连锁不平衡。

描述多样性

[编辑]| 遗传学 |

|---|

|

Neutral theory predicts that the level of nucleotide diversity in a population will be proportional to the product of the population size and the neutral mutation rate. The fact that levels of genetic diversity vary much less than population sizes do is known as the "paradox of variation".[66] While high levels of genetic diversity were one of the original arguments in favor of neutral theory, the paradox of variation has been one of the strongest arguments against neutral theory.

中性进化理论认为种群内的遗传多样性应与有效种群大小成正比,而在实际调查中,种群遗传多样性的差异程度远小于种群规模之差异的现象被称为"遗传差异的悖论"(paradox of variation)。

Neutral theory predicts that the level of nucleotide diversity in a population will be proportional to the product of the population size and the neutral mutation rate. The fact that levels of genetic diversity vary much less than population sizes do is known as the "paradox of variation".[66] While high levels of genetic diversity were one of the original arguments in favor of neutral theory, the paradox of variation has been one of the strongest arguments against neutral theory.

性状由遗传和环境的交互作用决定。多样性的来源包括基因、环境和和两者的交互作用。照定义,只有可遗传的部分会影响生物进化,所以群体遗传学主要用等位基因的频率来表示生物多样性,并追踪其变化来了解一个性状的进化。一个种群中,某个性状的多样性源自遗传差异的比例,称为可遗传性(heritability)。

连锁不平衡

[编辑]当基因座之间彼此独立时,一个个体共时带有A基因和B基因的几率f(AB)应该要等于f(A)×f(B)。但是有些进化动力或分子机制会造成基因座之间不独立。连锁不平衡描述的就是不同基因座之间,某些基因非随机共同出现的几率。[43]

- f(AB) = f(A)f(B) + D

- f(Ab) = f(A)f(b) - D

- f(aB) = f(a)f(B) - D

- f(ab) = f(a)f(b) + D

D即是A和B之间的连锁不平衡。也可以用如下公式计算:

- D = f(AB)f(ab) - f(Ab)f(aB)

检测选择压力

[编辑]遗传系统进化

[编辑]参见

[编辑]参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Linnaeus 1753.

- ^ Ohba 1977.

- ^ Fu & Ohba 2001,第221页.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Mort et al 2001.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Nikulin et al 2016.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Thiede & Eggli 2007.

- ^ Hart 1985.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 van Ham & Hart 1998.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Ohba et al 2000.

- ^ Fu & Ohba 2001,第220页.

- ^ ICN 2019.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Messerschmid et al 2020.

- ^ Hart & Jarvis 1993.

- ^ de Candolle 1828.

- ^ Gray 1821.

- ^ Praeger 1921.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Berger 1930.

- ^ Fröderströmm 1935.

- ^ Ohba 1978.

- ^ Tutin et al 1993.

- ^ Uhl 1978.

- ^ Ito et al 2017.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Hart & Alpinar 1991.

- ^ Hart 1995.

- ^ Hart 1995a.

- ^ Hart 1997.

- ^ Ding et al 2019.

- ^ TPL 2013.

- ^ van Ham et al 1994.

- ^ Gallo 2017.

- ^ Gallo 2017a.

- ^ Gallo & Zika 2014.

- ^ Hart 2003,p. 41.

- ^ WFO 2019.

- ^ Mort et al 2009.

- ^ Kim, Hyoung Tae; Lim, Ki-Byung; Kim, Jung Sung. New Insights on Lilium Phylogeny Based on a Comparative Phylogenomic Study Using Complete Plastome Sequences. Plants. 2019-11-27, 8 (12): 547. doi:10.3390/plants8120547.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第156页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第208-209页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第95-97页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第105-111页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第121页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第48-49页.

- ^ Hartl & Clark 2007,第77-78页.

参考书目

[编辑]- Gillespie, John. Population Genetics: A Concise Guide. Johns Hopkins Press. 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5755-4.

- Hartl, Daniel. Primer of Population Genetics 4. Sinauer. 2007. ISBN 978-0-87893-308-2.

- Hartl, Daniel; Clark, Andrew. Principles of Population Genetics 3. Sinauer. 1997. ISBN 0-87893-306-9.

引用错误:页面中存在<ref group="lower-alpha">标签或{{efn}}模板,但没有找到相应的<references group="lower-alpha" />标签或{{notelist}}模板