用户:JuneAugust/临时文字

T1

[编辑]相关条目、注释、参考文献、延伸阅读

T2

[编辑]伊52の派遣の目的は伊30号により持ち帰ったドイツ制工业制品の制造技术の取得のために派遣された。当舰に便乘していたのは主に民间の技术者で ある。ドイツへの技术供与の対価として2トンの金块、および当时のドイツで不足していたスズ・モリブデン・タングステンなど计228トンが积载されてい た。

アメリカ军は访独潜水舰作戦に特别な関心を示し日本とドイツ间で交わされる无线を傍受、その动きを追い続けていた。 イ52は无线交信では“モミ”と呼ばれていた。

————————

用户:JuneAugust/伊号第五二潜水舰

T3

[编辑]http://homepage1.nifty.com/kitabatake/rikukaiguntop.html

T4

[编辑]帝国陆军编制総覧

T5

[编辑][1] http://wenku.baidu.com/view/cecdd086ec3a87c24028c4c1.html

T6

[编辑]

T7

[编辑]javascript:(function%20(s)%20{%20s.src="https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=User:%E5%96%B5/langlinks_replace.js&action=raw";%20document.body.appendChild(s);%20})(document.createElement("script"))

T8

[编辑]国语配音名单

基拉·大和/于正升 亚斯兰·萨拉/丘台名、王瑞芹(幼年) 拉克丝·克莱因/詹雅菁 卡嘉丽·尤拉·阿斯哈/詹雅菁 芙蕾·阿露斯达/林美秀 美莉亚·赫/林美秀 赛·阿盖尔/熊肇川 托尔·寇尼希/丘台名 卡兹·巴斯卡克/詹雅菁 玛琉·拉米亚斯/王瑞芹→詹雅菁 娜塔尔·巴基露露/詹雅菁 穆·拉·布拉加/熊肇川 劳·卢·克鲁谢/熊肇川→于正升 伊撒古·玖尔/于正升 迪亚加·艾尔斯曼/丘台名 尼哥路·阿玛菲/林美秀 安德烈·巴特菲尔德/梁兴昌 米盖尔·艾曼/熊肇川

T9

[编辑] Constitution under sail, 19 August 2012

| |

| 历史 | |

|---|---|

| 舰名 | USS Constitution |

| 舰名出处 | United States Constitution[1] |

| 下订日 | 1 March 1794 |

| 建造者 | Edmund Hartt's Shipyard |

| 原始造价 | $302,718 (1797)[2] |

| 铺设龙骨 | 1 November 1794 |

| 下水日期 | 21 October 1797 |

| 首航日期 | 22 July 1798[3] |

| 更名 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) Old Constitution 1917 Constitution 1925 |

| 重新归类 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) IX-21, 1941 No classification, 1 September 1975 |

| 母港 | Charlestown Navy Yard[2] |

| 绰号 | "Old Ironsides" |

| 目前状态 | In active service |

| 船徽 |

|

| 技术数据(As built ca. 1797) | |

| 船型 | 44-gun frigate |

| 吨位 | 1,576[4] |

| 排水量 | 2,200 tons[4] |

| 船长 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) 204英尺(62米) billet head to taffrail; 175英尺(53米) at waterline[2] |

| 型宽 | 43英尺6英寸(13.26米) |

| 高度 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) foremast: 198英尺(60米) mainmast: 220英尺(67米) mizzenmast:172.5英尺(52.6米)[2] |

| 吃水 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) 21英尺(6.4米) forward 23英尺(7.0米) aft[4] |

| 舱深 | 14英尺3英寸(4.34米)[1] |

| 甲板 | Orlop, Berth, Gun, Spar |

| 动力来源 | Sail (three masts, ship rig) |

| 帆索方案 | 42,710 sq ft(3,968 m2) on three masts[2] |

| 船速 | 13节(24千米每小时;15英里每小时)[1] |

| 舰载船 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) 1 × 36英尺(11米) longboat 2 × 30英尺(9.1米) cutters 2 × 28英尺(8.5米) whaleboats 1 × 28英尺(8.5米) gig 1 × 22英尺(6.7米) jolly boat 1 × 14英尺(4.3米) punt[2] |

| 乘员 | 450 including 55 Marines and 30 boys (1797)[2] |

| 武器装备 |

列表错误:<br /> list(帮助) 30 × 24-pounder (11 kg) long gun 20 × 32-pounder (15 kg) carronade 2 × 24-pounder (11 kg) bow chasers[2] |

USS Constitution | |

| 地点 | Boston Naval Shipyard, Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| 占地面积 | less than one acre |

| 建于 | 1797 |

| NRHP编号 | 66000789[5] |

| NRHP收录 | 15 October 1966 |

USS Constitution is a wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate of the United States Navy. Named by President George Washington after the Constitution of the United States of America, she is the world's oldest commissioned naval vessel afloat.[Note 1] Launched in 1797, Constitution was one of six original frigates authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794 and the third constructed. Joshua Humphreys designed the frigates to be the young Navy's capital ships, and so Constitution and her sisters were larger and more heavily armed and built than standard frigates of the period. Built in Boston, Massachusetts, at Edmund Hartt's shipyard, her first duties with the newly formed United States Navy were to provide protection for American merchant shipping during the Quasi-War with France and to defeat the Barbary pirates in the First Barbary War.

Constitution is most famous for her actions during the War of 1812 against Great Britain, when she captured numerous merchant ships and defeated five British warships: “Guerriere”号1806 (6), “Java”号1811 (2), “Pictou”号1813 (2), “Cyane”号1806 (2) and “Levant”号1813 (2). The battle with Guerriere earned her the nickname of "Old Ironsides" and public adoration that has repeatedly saved her from scrapping. She continued to serve as flagship in the Mediterranean and African squadrons, and circled the world in the 1840s. During the American Civil War, she served as a training ship for the United States Naval Academy. She carried US artwork and industrial displays to the Paris Exposition of 1878.

Retired from active service in 1881, Constitution served as a receiving ship until designated a museum ship in 1907. In 1934 she completed a three-year, 90-port tour of the nation. Constitution sailed under her own power for her 200th birthday in 1997, and again in August 2012, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of her victory over Guerriere.

Constitution's stated mission today is to promote understanding of the Navy's role in war and peace through educational outreach, historic demonstration, and active participation in public events. As a fully commissioned US Navy ship, her crew of 60 officers and sailors participate in ceremonies, educational programs, and special events while keeping the ship open to visitors year round and providing free tours. The officers and crew are all active-duty US Navy personnel and the assignment is considered special duty in the Navy. Traditionally, command of the vessel is assigned to a Navy Commander. Constitution is berthed at Pier 1 of the former Charlestown Navy Yard, at one end of Boston's Freedom Trail.

Construction

[编辑]In 1785 Barbary pirates, most notably from Algiers, began to seize American merchant vessels in the Mediterranean. In 1793 alone, eleven American ships were captured and their crews and stores held for ransom. To combat this problem, proposals were made for warships to protect American shipping, resulting in the Naval Act of 1794.[7][8] The act provided funds to construct six frigates, but included a clause that if peace terms were agreed to with Algiers, the construction of the ships would be halted.[9][10]

Joshua Humphreys' design was unusual for the time, being long on keel and narrow of beam (width) and mounting very heavy guns. The design called for a diagonal scantling (rib) scheme intended to restrict hogging while giving the ships extremely heavy planking. This design gave the hull a greater strength than a more lightly built frigate. Humphreys' design was based on his realization that the fledgling United States of the period could not match the European states in the size of their navies. This being so, the frigates were designed to be able to overpower any other frigate yet escape from a ship of the line.[11][12][13]

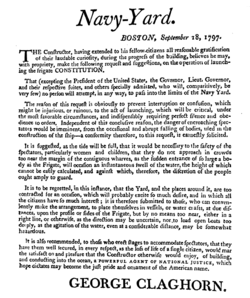

The name Constitution was selected by President George Washington.[14] Her keel was laid down on 1 November 1794 at Edmund Hartt's shipyard in Boston, Massachusetts, under the supervision of Captain Samuel Nicholson and naval constructor Colonel George Claghorn.[15][16] Primary materials used in her construction consisted of pine and oak, including southern live oak, which was cut and milled near St. Simons, Georgia.[16] Constitution's hull was built 21英寸(530毫米) thick and her length between perpendiculars was 175英尺(53米), with a 204英尺(62米) length overall and a width of 43英尺6英寸(13.26米).[2][4] In total, 60英亩(24公顷) of trees were needed for her construction.[17] Paul Revere forged the copper bolts and breasthooks.[18] The copper sheathing, installed to prevent shipworm, was imported from England.[19][Note 2]

In March 1796, as construction slowly progressed, a peace accord was announced between the United States and Algiers and, in accordance with the Naval Act of 1794, construction was halted.[21] After some debate and prompting by President Washington, Congress agreed to continue to fund the construction of the three ships nearest to completion: “United States”号1797 (2), “Constellation”号1797 (2), and Constitution.[22][23] Constitution's launching ceremony on 20 September 1797 was attended by then President John Adams and Massachusetts Governor Increase Sumner. Upon launch, she slid down the ways only 27英尺(8.2米) before stopping; her weight had caused the ways to settle into the ground, preventing further movement. An attempt two days later resulted in only an additional 31英尺(9.4米) of travel before the ship again stopped. After a month of rebuilding the ways, Constitution finally slipped into Boston Harbor on 21 October 1797, with Captain James Sever breaking a bottle of Madeira wine on her bowsprit.[24][25]

Armament

[编辑]Though rated as a 44-gun frigate, Constitution would often carry over 50 guns at a time.[26] Ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns, such as modern Navy ships carry. The guns and cannons were designed to be completely portable, and often were exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer outfitted armaments to his liking, taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, the armaments on ships would change often during their careers, and records of the changes were not generally kept.[27]

During the War of 1812, Constitution's battery of guns typically consisted of thirty 24-pounder (11 kg) cannons, with 15 on each side of the gun deck. Twenty-two 32-pounder (15 kg) carronades on the spar deck were deployed 11 per side. Four chase guns were also positioned, two each at the stern and bow.[28]

Since her 1927–1931 restoration, all of the guns aboard Constitution are replicas. Most were cast in 1930, but two carronades on the spar deck were cast in 1983.[29] In order to restore the capability of firing ceremonial salutes, during her 1973–1976 restoration, a modern 40 mm(1.6英寸) saluting gun was hidden inside the forward long gun on each side.[30]

Quasi-War

[编辑]President John Adams ordered all Navy ships to sea in late May 1798 to patrol for armed ships of France, and to free any American ship captured by them. Constitution was still not ready to sail, and eventually had to borrow sixteen 18-pound (8.2 kg) cannons from Castle Island before finally being ready.[3] Constitution put to sea on the evening of 22 July 1798 with orders to patrol the Eastern seaboard between New Hampshire and New York. A month later she was patrolling between Chesapeake Bay and Savannah, Georgia, when Nicholson found his first opportunity for capturing a prize: off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, on 8 September, she intercepted Niger, a 24-gun ship sailing with a French crew en route from Jamaica to Philadelphia, claiming to have been under the orders of Great Britain.[31] Perhaps not understanding his orders correctly, Nicholson had the crewmen imprisoned, placed a prize crew aboard Niger, and brought her into Norfolk, Virginia. Constitution sailed south again a week later to escort a merchant convoy, but her bowsprit was severely damaged in a gale; she returned to Boston for repairs. In the meantime, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert determined that Niger had been operating under the orders of Great Britain as claimed, and the ship and her crew were released to continue their voyage. The American government paid a restitution of $11,000 to Great Britain.[32][33]

After departing from Boston on 29 December, Nicholson reported to Commodore John Barry, who was flying his flag in United States, near the island of Dominica for patrols in the West Indies. On 15 January 1799, Constitution intercepted the English merchantman Spencer, which had been taken prize by the French frigate L'Insurgente a few days prior. Technically, Spencer was a French ship operated by a French prize crew; but Nicholson, perhaps hesitant after the affair with Niger, released the ship and her crew the next morning.[34][35] Upon joining Barry's command, Constitution almost immediately had to put in for repairs to her rigging due to storm damage, and it was not until 1 March that anything of note occurred. On this date, she encountered “Santa Margarita”号1779 (6),[36][37] the captain of which was an acquaintance of Nicholson. The two agreed to a sailing duel, which the English captain was confident he would win. But after 11 hours of sailing Santa Margarita lowered her sails and admitted defeat, paying off the bet with a cask of wine to Nicholson.[38][Note 3] Resuming her patrols, Constitution managed to recapture the American sloop Neutrality on 27 March and, a few days later, the French ship Carteret. Secretary Stoddert had other plans, however, and recalled Constitution to Boston. She arrived there on 14 May, and Nicholson was relieved of command.[39]

Change of command

[编辑]Captain Silas Talbot was recalled to duty to command Constitution and serve as Commodore of operations in the West Indies. After repairs and resupply were completed, Constitution departed Boston on 23 July with a destination of Saint-Domingue via Norfolk and a mission to interrupt French shipping. She took the prize Amelia from a French prize crew on 15 September, and Talbot sent the ship back to New York City with an American prize crew. Constitution arrived at Saint-Domingue on 15 October and rendezvoused with “Boston”号1799 (2), “General Greene”号1799 (2), and “Norfolk”号1798 (2). No further incidents occurred over the next six months, as French depredations in the area had declined. Constitution busied herself with routine patrols and Talbot made diplomatic visits.[40] It was not until April 1800 that Talbot investigated an increase in ship traffic near Puerto Plata, Santo Domingo, and discovered that the French privateer Sandwich had taken refuge there. On 8 May the squadron captured the sloop Sally, and Talbot hatched a plan to capture Sandwich by utilizing the familiarity of Sally to allow the Americans access to the harbor.[41] First Lieutenant Isaac Hull led 90 sailors and Marines into Puerto Plata without challenge on 11 May, capturing Sandwich and spiking the guns of the nearby Spanish fort.[42] However, it was later determined that Sandwich had been captured from a neutral port; she was returned to the French with apologies, and no prize money was awarded to the squadron.[43][44]

Routine patrols again occupied Constitution for the next two months, until 13 July, when the mainmast trouble of a few months before recurred. She put into Cap Francois for repairs. With the terms of enlistment soon to expire for the sailors aboard her, she made preparations to return to the United States, and was relieved of duty by Constellation on 23 July. Constitution escorted twelve merchantmen to Philadelphia on her return voyage, and on 24 August put in at Boston, where she received new masts, sails, and rigging. Even though peace was imminent between the United States and France, Constitution again sailed for the West Indies on 17 December as squadron flagship, rendezvousing with “Congress”号1799 (2), “Adams”号1799 (2), “Augusta”号1799 (2), “Richmond”号1798 (2), and “Trumbull”号1799 (2). Although no longer allowed to pursue French shipping, the squadron was assigned to protect American shipping and continued in that capacity until April 1801, when “Herald”号1798 (2) arrived with orders for the squadron to return to the United States. Constitution returned to Boston, where she lingered; she was finally scheduled for an overhaul in October, but it was later canceled. She was placed in ordinary on 2 July 1802.[45]

First Barbary War

[编辑]During the United States' preoccupation with France and the Quasi-War, troubles with the Barbary States were suppressed by the payment of tribute to ensure that American merchant ships were not harassed and seized.[46] In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute he was receiving in comparison to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000, equal to $4,724,500 today.[47] In response, Thomas Jefferson sent a squadron of frigates to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and to pursue peace with the Barbary States.[48][49]

The first squadron, under the command of Richard Dale in “President”号1800 (2), was instructed to escort merchant ships through the Mediterranean and negotiate with leaders of the Barbary States.[48] A second squadron was assembled under the command of Richard Valentine Morris in “Chesapeake”号1799 (2). The performance of Morris's squadron was so poor that he was recalled and subsequently dismissed from the Navy in 1803.[50]

Captain Edward Preble recommissioned Constitution on 13 May 1803 as his flagship, and made preparations to command a new squadron for a third blockade attempt. The copper sheathing on Constitution's hull needed to be replaced; Paul Revere supplied the copper sheets necessary for the job.[19][51] Constitution departed Boston on 14 August. On 6 September, near the Rock of Gibraltar, she encountered an unknown ship in the darkness. Constitution went to general quarters, then ran alongside of her. Preble hailed the unknown ship, only to receive a hail in return. After identifying his ship as the United States frigate Constitution, he received the same question again. Preble, losing his patience, said: "I am now going to hail you for the last time. If a proper answer is not returned, I will fire a shot into you." The stranger returned, "If you give me a shot, I'll give you a broadside." Asking once more, Preble demanded an answer, to which he received, "This is His Britannic Majesty's ship Donegal, 84 guns, Sir Richard Strachan, an English commodore," as well as a command to "Send your boat on board." Preble, now devoid of all patience, exclaimed, "This is United States ship Constitution, 44 guns, Edward Preble, an American commodore, who will be damned before he sends his boat on board of any vessel." And then to his gun crews: "Blow your matches, boys!"[Note 4] Before the incident escalated further, a boat arrived from the other ship and a British lieutenant relayed his Captain's apologies. The ship was in fact not Donegal but instead “Maidstone”号1797 (6), a 32-gun frigate. Constitution had come alongside her so quietly that Maidstone had delayed answering with the proper hail while she readied her guns.[52] This act began the strong allegiance between Preble and the officers under his command, known as "Preble's boys", as he had shown he was willing to defy a presumed ship of the line.[53][54]

Arriving at Gibraltar on 12 September, Preble waited for the other ships of the squadron. His first order of business was to arrange a treaty with Sultan Slimane of Morocco, who was holding American ships hostage to ensure the return of two vessels the Americans had captured. Departing Gibraltar on 3 October, Constitution and “Nautilus”号1799 (2) arrived at Tangiers on the 4th. “Adams”号1799 (2) and “New York”号1800 (2) arrived the next day. With four American warships in his harbor, the Sultan was more than glad to arrange the transfer of ships between the two nations, and Preble departed with his squadron on 14 October, heading back to Gibraltar.[55][56][57]

Battle of Tripoli Harbor

[编辑]

On 31 October “Philadelphia”号1799 (2), under the command of William Bainbridge, ran aground off Tripoli while pursuing a Tripoline vessel. The crew was taken prisoner; Philadelphia was refloated by the Tripolines and brought into their harbor.[58][59] To deprive the Tripolines of their prize, Preble planned to destroy Philadelphia using the captured ship Mastico, which was renamed “Intrepid”号1798 (2). Under the command of Stephen Decatur, Intrepid entered Tripoli Harbor on 16 February 1804 disguised as a merchant ship. Decatur's crew quickly overpowered the Tripoline crew and set Philadelphia ablaze.[60][61]

Withdrawing the squadron to Syracuse, Sicily, Preble began planning for a summer attack on Tripoli, procuring a number of smaller gunboats that could move in closer to Tripoli than was feasible for Constitution given her deep draft.[62] Arriving the morning of 3 August, Constitution, “Argus”号1803 (2), “Enterprise”号1799 (2), “Scourge”号1804 (2), “Syren”号1803 (2), the six gunboats, and two bomb ketches began operations. Twenty-two Tripoline gunboats met them in the harbor and, in a series of attacks in the coming month, Constitution and her squadron severely damaged or destroyed the Tripoline gunboats, taking their crews prisoner. Constitution primarily provided gunfire support, bombarding the shore batteries of Tripoli. Yet despite his losses, Karamanli remained firm in his demand for ransom and tribute.[63][64]

In a last attempt of the season against Tripoli, Preble outfitted Intrepid as a "floating volcano" with 100 short ton(91 t) of gunpowder aboard. She was to sail into Tripoli harbor and blow up in the midst of the corsair fleet, close under the walls of the city. Under the command of Richard Somers, Intrepid made her way into the harbor on the evening of 3 September, but exploded prematurely, killing Somers and his entire crew of thirteen volunteers.[65][66]

Constellation and President arrived at Tripoli on the 9th with Samuel Barron in command; Preble was forced to relinquish his command of the squadron to Barron, who was senior in rank.[67] Constitution was ordered to Malta on the 11th for repairs, and while en route captured two Greek vessels attempting to deliver wheat into Tripoli.[68] On the 12th, a collision with President severely damaged Constitution's bow, stern, and figurehead of Hercules. The collision was attributed to an "act of God", in the form of a sudden change in wind direction.[69][70]

Peace treaty

[编辑]Captain John Rodgers assumed command of Constitution on 9 November while she underwent repairs and resupply in Malta, and resumed the blockade of Tripoli on 5 April 1805, capturing a Tripoline xebec and the two prizes she had captured.[71] Meanwhile, Commodore Barron gave William Eaton naval support to bombard Derne, while a detachment of US Marines under the command of Presley O'Bannon was assembled to attack the city by land. They captured it on 27 April.[72] A peace treaty with Tripoli was signed aboard Constitution on 3 June, in which she embarked the crewmembers of Philadelphia and returned them to Syracuse.[73] Dispatched to Tunis, Constitution arrived there on 30 July, and by 1 August seventeen additional American warships had gathered in its harbor: Congress, Constellation, Enterprise, “Essex”号1799 (2), “Franklin”号1795 (2), “Hornet”号1805 sloop (2), “John Adams”号1799 (2), Nautilus, Syren, and eight gunboats. Negotiations went on for several days until a short-term blockade of the harbor finally produced a peace treaty on 14 August.[74][75]

Rodgers remained in command of the squadron, tasked with sending warships back to the United States when they were no longer needed. Eventually all that remained were Constitution, Enterprise, and Hornet. They performed routine patrols and observed the French and Royal Navy operations of the Napoleonic Wars.[76] Rodgers turned command of the squadron and Constitution over to Captain Hugh G. Campbell on 29 May 1806.[77]

James Barron and Chesapeake sailed out of Norfolk on 15 May 1807 to replace Constitution as the flagship of the Mediterranean squadron, but soon encountered “Leopard”号1790 (6), resulting in the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. Relief of Constitution was thereby delayed.[78] Constitution continued patrols, unaware of the delay. She arrived in late June at Leghorn, where she took aboard the disassembled Tripoli Monument for transport back to the United States. Arriving at Málaga, she learned the fate of Chesapeake. Campbell immediately began preparing Constitution and Hornet for possible war against England. The crew, upon learning of the delay in their relief, became mutinous and refused to sail any further unless the destination was the United States. Campbell and his officers threatened to fire a cannon full of grape shot at the crewmen if they did not comply, thereby putting an end to the conflict. Ordered home on 18 August, Campbell and the squadron set sail for Boston on 8 September, arriving there on 14 October. Constitution had been gone over four years.[79][80]

War of 1812

[编辑]

Constitution was recommissioned in December with Captain John Rodgers again taking command to oversee a major refitting. She was overhauled at a cost just under $100,000 (equal to $1,852,745 today); however, Rodgers inexplicably failed to clean her copper sheathing, leading him to later declare her a "slow sailer". She spent most of the following two years on training runs and ordinary duty.[81] When Isaac Hull took command in June 1810, he immediately recognized that she needed her bottom cleaned. "Ten waggon loads" of barnacles and seaweed were removed.[82]

Hull departed on 5 August 1811 for France, transporting the new Ambassador Joel Barlow and his family; they arrived on 1 September. During her visit in Cherbourg, Constitution was examined by French engineers, who reported her qualities to Denis Decrès, comparing her to the similar French 24-pounder frigate Forte; Decrès ordered construction of 24-pounder frigates to resume, but the fall of the Empire occurred only a few months later.[83] Remaining near France and Holland through the winter months, Hull continually held sail and gun drills to keep the crew ready for possible hostilities with the British. After the events of the Little Belt Affair the previous May, tensions were high between the United States and Britain, and Constitution was shadowed by British frigates while awaiting dispatches from Barlow to carry back to the United States. They arrived home on 18 February 1812.[84][85]

War was declared on 18 June and Hull put to sea on 12 July, attempting to join the five ships of a squadron under the command of Rodgers in “President”号1800 (2). Hull sighted five ships off Egg Harbor, New Jersey, on 17 July and at first believed them to be Rodgers' squadron, but by the following morning the lookouts determined that they were a British squadron out of Halifax: “Aeolus”号1801 (6), “Africa”号1781 (2), “Belvidera”号1809 (2), “Guerriere”号1806 (2), and “Shannon”号1806 (2). They had sighted Constitution and were giving chase.[86][87]

Finding himself becalmed, Hull acted on a suggestion given by Charles Morris, ordering the crew to put boats over the side to tow the ship out of range, using kedge anchors to draw the ship forward, and wetting the sails down to take advantage of every breath of wind.[88] The British ships soon imitated the tactic of kedging and remained in pursuit. The resulting 57 hour chase in the July heat saw the crew of Constitution employ a myriad of methods to outrun the squadron, finally pumping overboard 2,300 US gal(8.7 kl) of drinking water.[89] Cannon fire was exchanged several times, though the British attempts fell short or over their mark, including an attempted broadside from Belvidera. On 19 July Constitution pulled far enough ahead of the British that they abandoned the pursuit.[90][91]

Constitution arrived in Boston on 27 July and remained there just long enough to replenish her supplies; Hull sailed without orders on 2 August to avoid being blockaded in port.[92] Heading on a northeast route towards the British shipping lanes near Halifax and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Constitution captured three British merchantmen, which Hull ordered burned rather than risk taking them back to an American port. On 16 August Hull was informed of the presence of a British frigate 100 nmi(190 km;120 mi) to the south and sailed in pursuit.[93][94]

Constitution vs. Guerriere

[编辑]

A frigate sighted on 19 August was determined to be “Guerriere”号1806 (6), with the words "Not The Little Belt" painted on her foretopsail.[95][Note 5] Guerriere opened fire upon entering range of Constitution, doing little damage. After a few exchanges of cannon fire between the ships Captain Hull maneuvered into an advantageous position and brought Constitution to within 25码(23米) of Guerriere. He then ordered a full double-loaded broadside of grape and round shot fired, which took out Guerriere's mizzenmast.[96][97] With her mizzenmast dragging in the water, Guerriere's maneuverability decreased and she collided with Constitution; her bowsprit becoming entangled in Constitution's mizzen rigging. This left only Guerriere's bow guns capable of effective fire. Hull's cabin caught fire from the shots, but the fire was quickly extinguished. With the ships locked together, both Captains ordered boarding parties into action, but due to heavy seas neither party was able to board the opposing ship.[98]

At one point the two ships rotated together counter-clockwise, with Constitution continuing to fire broadsides. When the two ships pulled apart, the force of the bowsprit's extraction sent shock waves through Guerriere's rigging. Her foremast soon collapsed, and that brought the mainmast down shortly afterward.[99] Guerriere was now a dismasted, unmanageable hulk, with close to a third of her crew wounded or killed, while Constitution remained largely intact. The British surrendered.[100]

Using his heavier broadsides and his ship's sailing ability, Hull had managed to surprise the British. Adding to their astonishment, many of their shot rebounded harmlessly off Constitution's hull. An American sailor reportedly exclaimed "Huzzah! her sides are made of iron!" and Constitution acquired the nickname "Old Ironsides".[101]

The battle left Guerriere so badly damaged that she was not worth towing to port. The next morning, after transferring the British prisoners onto the Constitution, Hull ordered Guerriere burned.[102] Arriving back in Boston on 30 August, Hull and his crew found that news of their victory had spread fast, and they were hailed as heroes.[103]

Constitution vs Java

[编辑]

On 8 September William Bainbridge, senior to Hull, took command of "Old Ironsides" and prepared her for another mission in British shipping lanes near Brazil. Sailing with “Hornet”号1805 brig (2) on 27 October, they arrived near São Salvador on 13 December, sighting “Bonne Citoyenne”号1796 (6) in the harbor.[104] Bonne Citoyenne was reportedly carrying $1,600,000 in specie to England, but her captain refused to leave the neutral harbor lest he lose his cargo. Leaving Hornet to await the departure of Bonne Citoyenne, Constitution sailed offshore in search of prizes.[105] On 29 December she met with “Java”号1811 (6) under Captain Henry Lambert, a frigate of the same class as the Guerriere, and at the initial hail from Bainbridge, Java answered with a broadside that severely damaged Constitution's rigging. She was able to recover, however, and returned a series of broadsides to Java. A shot from Java destroyed Constitution's helm (wheel), so Bainbridge—wounded twice during the battle—directed the crew to steer her manually using the tiller for the remainder of the engagement.[106] As in the battle with Guerriere, Java's bowsprit became entangled in Constitution's rigging, allowing Bainbridge to continue raking her with broadsides. Java's foremast collapsed, sending her fighting top crashing down through two decks below.[107]

Drawing off to make emergency repairs, Bainbridge re-approached Java an hour later. As in the case with Guerriere, Java lay in shambles, an unmanageable wreck with a badly wounded crew. The British ship surrendered.[108] Determining that Java was far too damaged to retain as a prize, Bainbridge ordered her burned, but not before having her helm salvaged and installed on Constitution.[109] On Constitution's return to São Salvador on 1 January 1813, she met with Hornet and that ship's two British prizes to disembark the prisoners of Java. Being far away from a friendly port and needing extensive repairs, Bainbridge ordered Constitution to sail for Boston on 5 January,[110] leaving Hornet behind to continue waiting for Bonne Citoyenne in the hopes that she would leave the harbor (she did not).[111] Constitution's victory over Java, the third British warship in as many months to be captured by the United States, prompted the British Admiralty to order its frigates not to engage the heavier American frigates one-on-one; only British ships of the line or squadrons were permitted to come close enough to these ships to attack.[112][113] Constitution arrived in Boston on 15 February to even greater celebrations than Hull had received a few months prior.[114]

Marblehead and blockade

[编辑]Bainbridge determined that Constitution required new spar deck planking and beams, masts, sails, and rigging, and replacement of her copper bottom. However, personnel and supplies were being diverted to the Great Lakes, causing shortages that would keep her in Boston intermittently with her sister ships Chesapeake, Congress, and President for the majority of the year.[115] Charles Stewart took command on 18 July and struggled to complete the construction and recruitment of a new crew.[116] Finally making sail on 31 December, she set course for the West Indies to harass British shipping, and by late March 1814 had captured five merchant ships and the 14-gun “Pictou”号1813 (6). She also pursued “Columbine”号1806 (6) and “Pique”号1800 (2), though both ships escaped after realizing she was an American frigate.[117]

Off the coast of Bermuda on 27 March, it was discovered that her mainmast had split, requiring immediate repair. Stewart set a course for Boston, where on 3 April two British ships “Junon”号1810 (6) and “Tenedos”号1812 (2), commenced pursuit. Stewart ordered drinking water and food to be cast overboard to lighten her load and gain speed, trusting that her mainmast would hold together long enough for her to make her way into Marblehead, Massachusetts.[118] The last item thrown overboard was the supply of spirits. Upon Constitution's arrival in the harbor, the citizens of Marblehead rallied in support, assembling what cannons they possessed at Fort Sewall, and the British called off the pursuit.[119] Two weeks later, Constitution made her way into Boston, where she remained blockaded in port until mid-December.[120]

HMS Cyane and HMS Levant

[编辑]Captain George Collier of the Royal Navy received command of the 50-gun “Leander”号1813 (6) and was sent to North America to deal with the American frigates that were causing losses to British merchant shipping.[121] Meanwhile, Charles Stewart saw his chance to escape from Boston Harbor and made it good on the afternoon of 18 December. The ship again set course for Bermuda.[122] Collier gathered a squadron consisting of Leander, “Newcastle”号1813 (2), and “Acasta”号1797 (2), and set off in pursuit, but was unable to overtake Constitution.[123]

On 24 December Constitution intercepted the merchantman Lord Nelson and placed a prize crew aboard. Lord Nelson's stores readily supplied a Christmas dinner for the crew of Constitution; she had left Boston not fully supplied.[122] Off Cape Finisterre on 8 February 1815, Stewart learned that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed, but realized that until it was ratified a state of war still existed. On 16 February Constitution captured the British merchantman Susanna with her cargo of animal hides valued at $75,000.[124] Sighting two British ships on 20 February, she gave chase to them. The two were Cyane and “Levant”号1813 (2), sailing in company.[125]

Cyane and Levant began a series of broadsides against Constitution, but Stewart outmaneuvered both of them. Forcing Levant to draw off for repairs, he concentrated fire on Cyane, which soon struck her colors.[125] Levant returned to engage Constitution, but once she saw that Cyane had been defeated she turned and attempted escape.[126] Constitution overtook her, and after several more broadsides she too struck her colors.[125] Stewart remained with his new prizes overnight while ordering repairs to all ships. Constitution had suffered little damage in the battle, though it was later discovered she had twelve 32-pound British cannonballs embedded in her hull, none of which had penetrated through.[127] Setting a course for the Cape Verde Islands, the trio arrived at Porto Praya on 10 March.[125]

The next morning Collier's squadron was spotted on a course for the harbor, and Stewart ordered all ships to sail immediately.[125] Stewart had until then been unaware of the pursuit by Collier.[128] Cyane was able to elude the squadron and make sail for America, where she arrived on 10 April, but Levant was overtaken and recaptured. While Collier's squadron was distracted with Levant, Constitution made another escape from overwhelming forces.[129]

Constitution set a course towards Guinea and then west towards Brazil, as Stewart had learned from the capture of Susanna that “Inconstant”号1783 (6) was transporting gold bullion back to England, and wanted her as a prize. Constitution put into Maranhão on 2 April to offload her British prisoners and replenish her drinking water.[130] While there, Stewart learned by rumor that the Treaty of Ghent had been ratified, and set course for America. Receiving verification of peace at San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 28 April, he set course for New York and arrived home on 15 May to large celebrations.[125] While Constitution emerged from the war undefeated, her sister ships Chesapeake and President were not so fortunate, having been captured in 1813 and 1815 respectively.[131][132] Constitution was moved to Boston and placed in ordinary in January 1816, sitting out the action of the Second Barbary War.[129]

Mediterranean Squadron

[编辑]In April 1820 Isaac Hull, commandant of the Charlestown Navy Yard, directed a refitting of Constitution to prepare her for duty with the Mediterranean Squadron. Joshua Humphreys' diagonal riders were removed to make room for two iron freshwater tanks, and timbers below the waterline along with the copper sheathing were replaced.[133] At the direction of Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson, she was also subjected to an unusual experiment in which manually operated paddle wheels were fitted to her hull. If stranded by calm seas, the paddle wheels were designed to propel her at up to 3节(5.6千米每小时;3.5英里每小时) by the crew using the ship's capstan.[134] Initial testing was successful, but Hull and the new commanding officer of Constitution, Jacob Jones, were reportedly unimpressed with paddle wheels on a US Navy ship; Jones had them removed and stowed in the cargo hold before he departed on 13 May 1821 for a three-year tour of duty in the Mediterranean.[129]

Constitution experienced an uneventful tour, sailing in company with “Ontario”号1813 (2) and “Nonsuch”号1813 (2), until the behavior of the crews during shore leave gave Jones a reputation as a Commodore who was lax in discipline. Weary of receiving complaints about the crews' antics while in port, the Navy ordered Jones to return, and Constitution arrived in Boston on 31 May 1824, upon which Jones was relieved of command.[135] Thomas Macdonough took command and sailed on 29 October for the Mediterranean under the direction of John Rodgers in “North Carolina”号1820 (2). With discipline restored, Constitution resumed uneventful duty. Macdonough resigned his command for health reasons on 9 October 1825.[136] Constitution put in for repairs during December and into January 1826, until Daniel Todd Patterson assumed command on 21 February. By August she had put into Port Mahon, suffering decay of her spar deck, and she remained there until temporary repairs were completed in March 1827. Constitution returned to Boston on 4 July 1828 and was placed in ordinary.[137][138]

Old Ironsides

[编辑]Built in an era when a wooden ship had an expected service life of ten to fifteen years,[139] Constitution was now thirty-one years old. A routine order for surveys of ships held in ordinary was requested by the Secretary of the Navy John Branch; the commandant of the Charlestown Navy Yard, Charles Morris, estimated a repair cost of over $157,000 (equal to $4,635,916 today) for Constitution.[140] On 14 September 1830, an article appeared in the Boston Advertiser that erroneously claimed the Navy intended to scrap Constitution.[141][Note 6] Two days later, Oliver Wendell Holmes' poem "Old Ironsides" was published in the same paper and later all over the country, igniting public indignation and inciting efforts to save "Old Ironsides" from the scrap yard. Secretary Branch approved the costs, and she began a leisurely repair period while awaiting completion of the drydock then under construction at the yard.[142] In contrast to the efforts to save Constitution, another round of surveys in 1834 found her sister ship Congress unfit for repair; she was unceremoniously broken up in 1835.[143][144]

On 24 June 1833 Constitution entered drydock in company of a crowd of observers, among them Vice President Martin Van Buren, Levi Woodbury, Lewis Cass, and Levi Lincoln. Captain Jesse Elliott, the new commander of the Navy yard, would oversee her reconstruction. With 30英寸(760 mm) of hog in her keel, Constitution remained in dry dock until 21 June 1834. This would be the first of many times that souvenirs were made from her old planking; Isaac Hull ordered walking canes, picture frames, and even a phaeton that was presented to President Andrew Jackson.[145] Meanwhile, Elliot directed the installation of a new figurehead of President Jackson under the bowsprit, which became a subject of much controversy due to Jackson's political unpopularity in Boston at the time.[146] Elliot, a Jacksonian Democrat,[147] received death threats. Rumors circulated about the citizens of Boston storming the navy yard to remove the figurehead themselves.[143][148]

A merchant captain named Samuel Dewey accepted a small wager as to whether he could complete the task of removal. Elliot posted guards on Constitution to ensure safety of the figurehead, but—using the noise of thunderstorms to mask his movements—Dewey crossed the Charles River in a small boat and managed to saw off most of Jackson's head.[149] The severed head made the rounds between taverns and meeting houses in Boston until Dewey personally returned it to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson; it remained on Dickerson's library shelf for many years.[150][151] The addition of busts to her stern depicting Isaac Hull, William Bainbridge, and Charles Stewart escaped controversy of any kind; the busts would remain in place for the next forty years.[152]

Mediterranean and Pacific Squadrons

[编辑]Elliot was appointed Captain of Constitution and got underway in March 1835 to New York, where he ordered repairs to the Jackson figurehead, avoiding a second round of controversy.[153] Departing on 16 March Constitution set a course for France to deliver Edward Livingston to his post as Minister. She arrived on 10 April and began the return voyage on 16 May, narrowly avoiding being wrecked off the Isles of Scilly due to the mistaken navigation of her Officer of the Deck.[154] She arrived back in Boston on 23 June, then sailed on 19 August to take her station as flagship in the Mediterranean, arriving at Port Mahon on 19 September. Her duty over the next two years was uneventful as she and United States made routine patrols and diplomatic visits. From April 1837 into February 1838 Elliot collected various ancient artifacts to carry back to America, adding various livestock during the return voyage. Constitution arrived in Norfolk on 31 July. Elliot was later suspended from duty for transporting livestock on a Navy ship.[155][156]

As flagship of the Pacific Squadron under the command of Captain Daniel Turner, she began her next voyage on 1 March 1839 with the duty of patrolling the western side of South America. Often spending months in one port or another, she visited Valparaíso, Callao, Paita, and Puna while her crew amused themselves with the beaches and taverns in each locality.[157] The return voyage found her at Rio de Janeiro, where Emperor Pedro II of Brazil visited her about 29 August 1841. Departing Rio, she collided with the ketch Queen Victoria, suffering minor damage, and returned to Norfolk on 31 October. On 22 June 1842 she was recommissioned under the command of Foxhall Alexander Parker for duty with the Home Squadron. After spending months in port she put to sea for three weeks during December, then was again put in ordinary.[155]

Around the world

[编辑]In late 1843, she was moored at Norfolk, serving as a receiving ship. Naval Constructor Foster Rhodes calculated it would require $70,000 to make her seaworthy. Acting Secretary David Henshaw faced a dilemma. His budget could not support such a cost, yet he could not allow the country's favorite ship to deteriorate. He turned to Captain John Percival. Known in the service as "Mad Jack", the captain traveled to Virginia and conducted his own survey of the ship's needs. He reported that the necessary repairs and upgrades could be done at a cost of $10,000. On 6 November, Henshaw told Percival to proceed without delay, but stay within his projected figure. After several months of labor, Percival reported Constitution ready for "a two or even a three year cruise."[158]

She got underway on 29 May, carrying Henry A. Wise, the new Ambassador to Brazil, and his family, arriving at Rio de Janeiro on 2 August after making two port visits along the way. Remaining there to pack away supplies for the planned journey, she sailed again on 8 September, making port calls at Madagascar, Mozambique, and Zanzibar, and arriving at Sumatra on 1 January 1845. Many of her crew began to suffer from dysentery and fevers, causing several deaths, which led Percival to set course for Singapore, arriving there 8 February. While in Singapore, Commodore Henry Ducie Chads of “Cambrian”号1841 (6) paid a visit to Constitution, offering what medical assistance his squadron could provide. Chads had been the Lieutenant of “Java”号1811 (6) when that ship surrendered to William Bainbridge thirty-three years earlier.[159]

Leaving Singapore, Constitution arrived at Turon, Cochinchina (present day Da Nang, Vietnam) on 10 May. Not long after, Percival was informed that a French missionary, Dominique Lefèbvre, was being held captive under sentence of death. Percival and a squad of Marines went ashore to speak with the local Mandarin. Percival demanded the return of Lefèbvre and took three local leaders hostage to ensure his demands were met. When no communication was forthcoming, he ordered the capture of three junks, which were brought to Constitution. Percival released the hostages after two days, attempting to show good faith towards the Mandarin, who had demanded their return.[160] During a storm the three junks escaped upriver; a detachment of Marines pursued and recaptured them. When the supply of food and water from shore was stopped, Percival gave in to another demand for the release of the junks in order to keep his ship supplied, expecting Lefèbvre to be released. Soon realizing that no return would be made, Percival ordered Constitution to depart on 26 May.[161]

Arriving at Canton, China, on 20 June, she spent the next six weeks there while Percival made shore and diplomatic visits. Again the crew suffered from dysentery due to poor drinking water, resulting in three more deaths by the time she reached Manila on 18 September. Spending a week there preparing to enter the Pacific Ocean, she sailed on 28 September for the Hawaiian Islands, arriving at Honolulu on 16 November. At Honolulu she found Commodore John D. Sloat and his flagship “Savannah”号1842 (2); Sloat informed Percival that Constitution was needed in Mexico, as the United States was preparing for war after the Texas Annexation. She provisioned for six months and sailed for Mazatlán, arriving there on 13 January 1846. She sat at anchor for over three months until she was finally allowed to sail for home on 22 April rounding Cape Horn on 4 July. Arriving in Rio de Janeiro, the ship's party learned that the Mexican War had begun on 13 May, soon after their departure from Mazatlán. She arrived home in Boston on 27 September and was placed in ordinary on 5 October.[162]

Mediterranean and African Squadrons

[编辑]

Constitution began a refitting in 1847 for duty with the Mediterranean Squadron. The figurehead of Andrew Jackson that had caused so much controversy fifteen years earlier was replaced with another, this time sans the top hat and with a more Napoleonic pose for Jackson. Captain John Gwinn commanded her on this voyage, departing on 9 December 1848 and arriving at Tripoli on 19 January 1849. She carried Daniel Smith McCauley and his family to Egypt. McCauley's wife gave birth en route to a son, who was named "Constitution Stewart McCauley". At Gaeta on 1 August she received onboard King Ferdinand II and Pope Pius IX, giving them a 21-gun salute. This was the first time a Pope set foot on American territory or its equivalent. At Palermo on 1 September, Captain Gwinn died of chronic gastritis and was buried near Lazaretto on the 9th. Captain Thomas Conover assumed command on the 18th and resumed routine patrolling for the rest of the tour. Heading home on 1 December 1850, she was involved in a severe collision with the English brig Confidence, which sank with the loss of her captain. The surviving crewmembers were carried back to America, where the Constitution was placed in ordinary at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in January 1851.[163]

Recommissioned on 22 December 1852 under the command of John Rudd, the Constitution carried Commodore Isaac Mayo for duty with the African Squadron, departing the yard on 2 March 1853 on a leisurely sail towards Africa, arriving there on 18 June. Making a diplomatic visit in Liberia, Mayo arranged a treaty between the Gbarbo and the Grebo tribes. Mayo had to resort to firing cannons into the village of the Gbarbo in order to get them to agree to the treaty. This may have been the last time that the Constitution fired her cannons in anger. Near Angola on 3 November, in what would be her last capture, Constitution took as a prize the American ship H. N. Gambrill, which had been determined to be involved in the slave trade.[164] About 22 June 1854, Mayo arranged another peace treaty between the leaders of Grahway and Half Cavally. The rest of her tour passed uneventfully and she sailed for home on 31 March 1855. She was diverted to Havana, Cuba, arriving there on 16 May. Departing there on the 24th, she arrived at Portsmouth Navy Yard and was decommissioned on 14 June, ending what was to be her last duty on the front lines.[165] In June 1853, her sister ship Constellation had been ordered broken up. Then part of her timbers would be used to construct the next “Constellation”号1854 (2).[166][167]

Civil War

[编辑]The last sailing frigate of the US Navy, “Santee”号1855 (2), had been launched in 1855. As steamships began service with the US Navy in growing numbers during the 1850s, many sail-powered ships were assigned to training duty.[168] Since the formation of the US Naval Academy in 1845, there had been a growing need for quarters in which to house the students. In 1857, Constitution was moved to drydock at the Portsmouth Navy Yard for conversion into a training ship. Some of the earliest known photographs of her were taken during this refitting, which added classrooms on her spar and gun decks. Reduced in armament to only 16 guns, her rating was changed to a "2nd rate ship." She was recommissioned on 1 August 1860 and moved from Portsmouth to the Naval Academy.[169][170]

At the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, Constitution was ordered to relocate farther north after threats had been made against her by Confederate sympathizers.[171] Several companies of Massachusetts volunteer soldiers were stationed aboard for her protection.[172] “R. R. Cuyler”号1860 (2) towed her to New York City, where she arrived on 29 April. She was subsequently relocated, along with the Naval Academy, to Fort Adams near Newport, Rhode Island, for the duration of the war. Her sister ship United States was abandoned by the Union and then captured by Confederate forces at the Gosport Shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia, leaving Constitution as the only remaining frigate of the original six frigates.[141][173]

During the war, to honor Constitution's tradition of service, the Navy bestowed the name “New Ironsides”号1862 (2) on an ironclad that was launched on 10 May 1862 as part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron and participated in the bombardment of Fort Sumter on 7 April 1863. However, New Ironsides's naval career was short-lived; she was destroyed by fire on 16 December 1865.[174] In August 1865, Constitution moved back to Annapolis, along with the rest of the Naval Academy. During the voyage she was allowed to drop her tow lines from the tug and continue alone under wind power. Despite her age, she was recorded running at 9节(17千米每小时;10英里每小时) and arrived at Hampton Roads ten hours ahead of the tug.[141]

Settling in again at the Academy, a series of upgrades was installed that included steam pipes and radiators to supply heat from shore along with gas lighting. From June to August each year she would depart with midshipmen for their summer training cruise and then return to operate for the rest of the year as a classroom. In June 1867 her last known plank owner, William Bryant, died in Maine. George Dewey assumed command in November and he served as her commanding officer until 1870. In 1871 her condition had deteriorated to the point where she was retired as a training ship, and then towed to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where she was placed in ordinary on 26 September.[175]

Paris Exposition

[编辑]

In the early months of 1873 it was decided that Constitution would be overhauled to participate in the centennial celebrations of the United States. Work began slowly and was intermittently delayed by the transition of the Philadelphia Navy Yard to League Island. By late 1875 the Navy opened bids for an outside contractor to complete her work, and Constitution was moved to Wood, Dialogue and Company in May 1876, where a small boiler for heat and a coal bin were installed. The Andrew Jackson figurehead was removed at this time and given to the Naval Academy Museum where it remains today.[176] Her construction dragged on during the rest of 1876, and when the centennial celebrations had long passed, it was decided that she would be used as a training and school ship for apprentices entering the Navy.[177]

Oscar C. Badger took command on 9 January 1878 to prepare her for a voyage to the Paris Exposition of 1878, transporting artwork and industrial displays of American manufacturers to France.[178] Three railroad cars were lashed to her spar deck and all but two cannons were removed when she departed on 4 March. While docking at Le Havre she collided with Ville de Paris, which resulted in Constitution entering dry dock for repairs. Remaining in France for the rest of 1878, she got underway for the United States on 16 January 1879, but poor navigation ran her aground the next day near Bollard Head. She was towed into the Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, Hampshire, England, where only minor damage was found and repaired.[179]

Her problem-plagued voyage would continue on 13 February when her rudder was damaged during heavy storms, resulting in a total loss of steering control. With the rudder smashing into the hull at random, three crewman went over the stern on ropes and boatswain's chairs and secured it. The next morning they rigged together a temporary steering system. Badger set a course for the nearest port, and she arrived in Lisbon on 18 February. Slow dock services delayed her departure until 11 April and her voyage home did not end until 24 May.[180] Crewmen Henry Williams, Joseph Matthews, and James Horton would receive the Medal of Honor for their actions in repairing the damaged rudder at sea.[181] Constitution returned to her previous duties of training apprentice boys,[182] and on 16 November another crewman, James Thayer, received a Medal of Honor for saving a boy from drowning.[181]

Over the next two years she continued her training cruises, but it soon became apparent that her overhaul in 1876 had been of poor quality, and she was determined to be unfit for service in 1881. As funds were lacking for another overhaul, she was decommissioned, ending her days as an active-duty naval ship. Moved to the Portsmouth Navy Yard, she was used as a receiving ship. There, she had a housing structure built over her spar deck, and her condition continued to deteriorate, with only a minimal amount of maintenance performed to keep her afloat.[169][183] In 1896, Massachusetts Congressman John F. Fitzgerald became aware of her condition and proposed to Congress that funds be appropriated to restore her enough to return to Boston.[184] She arrived at the Charlestown Navy Yard under tow on 21 September 1897,[185] and after her centennial celebrations in October, she lay there with an uncertain future.[169][186]

Museum ship

[编辑]

In 1900 Congress authorized restoration of Constitution, but did not appropriate any funds for the project; funding was to be raised privately. The Massachusetts Society of the United Daughters of the War of 1812 spearheaded an effort to raise funds, but ultimately failed.[187] In 1903 the Massachusetts Historical Society's president Charles Francis Adams requested of Congress that she be rehabilitated and placed back into active service.[188]

In 1905, Secretary of the Navy Charles Joseph Bonaparte suggested that she be towed out to sea and used as target practice, after which she would be allowed to sink. Reading about this in a Boston newspaper, Moses H. Gulesian, a businessman from Worcester, Massachusetts, offered to purchase Constitution for $10,000.[187][189] The State Department refused, but Gulesian initiated a public campaign which began from Boston and ultimately "spilled all over the country."[189] The storms of protest from the public prompted Congress to authorize $100,000 for her restoration in 1906. First to be removed was the barracks structure on her spar deck, but the limited amount of funds allowed just a partial restoration.[190] By 1907 she began to serve as a museum ship with tours offered to the public. On 1 December 1917 she was renamed Old Constitution, to free her name for a planned new Lexingtonbattlecruiser. Originally destined for the lead ship of the class, the name Constitution was shuffled around between hulls until CC-5 was given the name; construction of CC-5 was canceled in 1923 due to the Washington Naval Treaty. The incomplete hull was sold for scrap, and Old Constitution was granted the return of her name on 24 July 1925.[1]

1925 restoration and tour

[编辑]Admiral Edward Walter Eberle, Chief of Naval Operations, ordered the Board of Inspection and Survey to compile a report on her condition, and the inspection of 19 February 1924 found her in grave condition. Water had to be pumped out of her hold on a daily basis just to keep her afloat, and her stern was in danger of falling off. Almost all deck areas and structural components were filled with rot, and she was considered to be on the verge of ruin. Yet the Board recommended that she be thoroughly repaired in order to preserve her as long as possible. The estimated cost of repairs was $400,000. Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur proposed to Congress that the required funds be raised privately, and he was authorized to assemble the committee charged with her restoration.[191][192]

The first effort was sponsored by the national Elks Lodge. Programs presented to schoolchildren about "Old Ironsides" encouraged them to donate pennies towards her restoration, eventually raising $148,000. In the meantime, the estimates for repair began to climb, eventually reaching over $745,000 after costs of materials were realized.[193] In September 1926, Wilbur began to sell copies of a painting of Constitution at 50 cents per copy. The silent film Old Ironsides, which portrayed Constitution during the First Barbary War, premiered in December and helped spur more contributions to her restoration fund. The final campaign allowed memorabilia to be made of her discarded planking and metal. Among the items sold were ashtrays, bookends and picture frames. The committee eventually raised over $600,000 after expenses—still short of the required amount—and Congress approved up to $300,000 to complete the restoration. The final cost of the restoration was $946,000.[194]

Lieutenant John A. Lord was selected to oversee the reconstruction project, and work began while efforts to raise funds were still underway. Materials were difficult to find, especially the live oak needed; Lord uncovered a long-forgotten stash of live oak (some 1,500 short ton(1,400 t)) at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida that had been cut sometime in the 1850s for a ship building program that never began. By the mid-1920s even the tools needed for the restoration were difficult to find, and some came from as far away as Maine. The Constitution entered drydock with a crowd of 10,000 observers on 16 June 1927. Meanwhile, Charles Francis Adams had been appointed as the Secretary of the Navy, and he proposed that the Constitution make a tour of the United States upon her completion as a gift to the nation for its efforts to help restore her. She emerged from drydock on 15 March 1930, and many amenities were installed to prepare her for the three-year tour of the country, including water piping throughout, modern toilet and shower facilities, electric lighting to make the interior visible for visitors, and several peloruses for ease of navigation.[195]

No stranger to controversy, Constitution experienced another episode when Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ernest Jahncke made comments doubting the ability of the modern US Navy to still sail a vessel of her type. Veterans groups from around the country had proposed that she should make the tour under sail, but due to the schedule of visits on her itinerary she was towed by the minesweeper “Grebe”号AM-43 (2).[192] Nevertheless, she was recommissioned on 1 July 1931 under the command of Louis J. Gulliver with a crew of sixty officers and sailors, fifteen Marines, and their mascot, a pet monkey named Rosie. Setting out with much celebration and a 21-gun salute, the tour of 90 port cities along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts began at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. She went as far north as Bar Harbor, Maine, on the Atlantic coast, south through the Panama Canal Zone, and north again to Bellingham, Washington, on the Pacific Coast. The Constitution returned to her home port of Boston in May 1934 after more than 4.6 million people had visited her during the three-year journey.[196]

Bicentennial celebrations

[编辑]Settled in Boston again, Constitution returned to serving as a museum ship, receiving 100,000 visitors per year. She was maintained by a small crew that watched over her and were berthed on the ship, requiring that a more reliable heating system be installed, eventually leading to a forced-air system in the 1950s and the addition of a sprinkler system that would help protect her from fire. On 21 September 1938 during the New England Hurricane, Constitution broke loose from her dock and was blown out into Boston Harbor where she collided with the destroyer “Ralph Talbot”号DD-390 (2); she suffered only minor damage.[197]

With limited funds available, she experienced more deterioration over the years, and items began to disappear from the ship as souvenir hunters picked away at the more portable objects.[198] In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed her in permanent commission. General Bruce Magruder gave the nickname "Old Ironsides" to the 1st Armored Division of the United States Army in honor of the ship.[199] In early 1941, she was assigned the hull classification symbol IX-21[1] and began to serve as a brig for officers awaiting court-martial. The United States Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating Constitution in 1947, and an act of Congress in 1954 made the Secretary of the Navy responsible for her upkeep.[200]

In 1970 another survey of her condition was performed, this time finding that repairs were required, but not as extensive as those she had needed in the 1920s. The US Navy determined that an officer of the rank of Commander—typically someone with about twenty years of seniority—would be required as commanding officer, so as to have the experience to organize the maintenance she required.[201] Funds were approved in 1972 for her restoration, and she entered drydock in April 1973, remaining until April 1974. During this period, large quantities of red oak were removed and replaced. The red oak had been added in the 1950s as an experiment to see if it would last better than the live oak, but it had mostly rotted away by 1970. Commander Tyrone G. Martin became her Captain in August 1974, as preparations for the upcoming United States Bicentennial celebrations began. Commander Martin set the precedent that all construction work on Constitution was to be aimed towards maintaining her to the 1812 configuration for which she is most famous.[202] In September 1975 her hull classification of IX-21 was officially canceled.[1]

The privately run USS Constitution Museum opened on 8 April 1976, and one month later Commander Martin dedicated a tract of land located at the Naval Surface Warfare Center in Indiana as "Constitution Grove." The 25,000英亩(100平方千米) now supply the majority of the white oak required for repair work.[203] On 10 July Constitution led the parade of tall ships up Boston Harbor for Operation Sail, firing her guns at one-minute intervals for the first time in approximately 100 years.[204] On the 11th she rendered a 21-gun salute to Her Majesty's Yacht Britannia as Her Majesty Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness Prince Philip arrived for a state visit.[205] Her Majesty and His Royal Highness were piped aboard and privately toured the ship for approximately thirty minutes with Commander Martin and Secretary of the Navy J. William Middendorf. Upon their departure the crew of Constitution rendered three cheers for the Queen. Over 900,000 visitors toured "Old Ironsides" that year.[206]

1995 reconstruction

[编辑]Constitution entered drydock in 1992 for an inspection and minor repair period that turned out to be her most comprehensive structural restoration and repair since she was launched in 1797. Over the 200 years of her career, as her mission changed from a fighting warship to a training ship and eventually a receiving ship, multiple refittings had removed most of her original construction components and design. In 1993 the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston reviewed Humphreys' original plans and identified five main structural components that were required to prevent hogging of a ship's hull,[207] as Constitution had at this point 13英寸(330 mm) of hog. Using a 1:16 scale model of the ship, they were able to determine that restoring the original components would result in a 10% increase in hull stiffness.[208]

Using radiography, a technique unavailable during previous reconstructions, 300 scans of her timbers were completed to find any hidden problems otherwise undetectable from the outside. Aided by the United States Forest Service's Forest Products Laboratory, the repair crew used sound wave testing to determine the condition of the remaining timbers that may have been rotting from the inside.[207] The 13英寸(330 mm) of hog was removed from her keel by allowing the ship to settle naturally while in dry dock. The most difficult task, as it had been during her 1920s restoration, was the procurement of timber in the quantity and sizes needed. The city of Charleston, South Carolina, donated live oak trees that had been felled by Hurricane Hugo in 1989, and the International Paper Company donated live oak from its own property.[203] The project continued to reconstruct her to 1812 specifications even as she remained open to visitors, who were allowed to observe the process and converse with workers.[207] The twelve million dollar project was completed in 1995.[209]

Sail 200

[编辑]As early as 1991, Commander David Cashman had suggested that Constitution should sail, rather than be towed, to celebrate her 200th anniversary in 1997. The proposal was approved, though it was thought to be a large undertaking since she had not sailed in over 100 years.[210] When she emerged from drydock in 1995, a more serious effort began to prepare her for sail. As in the 1920s, education programs aimed at school children helped collect pennies to purchase the sails to make the voyage possible. Eventually her six-sail battle configuration would consist of jibs, topsails, and driver.[211]

Commander Mike Beck began training the crew for the historic sail using an 1819 Navy sailing manual and several months of practice, including time spent aboard the Coast Guard cutter Eagle.[212] On 19 July 1997 a free showing of the classic silent film Old Ironsides was given, with the film accompanist, organist Dennis James, using original materials by Hugo Riesenfeld, and period scores. During the scene depicting its battle with the Guerriere, the ship's actual cannon were fired in sync with the film.[213] The next day, on 20 July, Constitution was towed from her usual berth in Boston to an overnight mooring in Marblehead, Massachusetts. En route she made her first sail in 116 years at a recorded 6节(11千米每小时;6.9英里每小时),[214][215] and was absent overnight from her berth in Charlestown for the first time since 1934. Embarked dignitaries included the Secretary of the Navy, Chief of Naval Operations, the Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, US Senator Ted Kennedy, US Senator John Kerry, and journalist and avid recreational sailor Walter Cronkite.[216]

The next day, 21 July, she was towed 5海里(9.3千米;5.8英里) offshore, where the tow line was dropped and Commander Beck ordered six sails set (jibs, topsails, and spanker). She then sailed for 40 minutes on a south-south-east course with true wind speeds of about 12 kn(22 km/h;14 mph), attaining a top recorded speed of 4 kn(7.4 km/h;4.6 mph).[216] While under sail, her modern US naval combatant escorts, the guided missile destroyer “Ramage”号DDG-61 (2) and frigate “Halyburton”号FFG-40 (2), rendered passing honors to "Old Ironsides", and she was overflown by the US Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels. Inbound to her permanent berth at Charlestown she rendered a 21-gun salute to the nation off Fort Independence in Boston Harbor.[211]

Present day

[编辑]The mission of Constitution is to promote understanding of the Navy's role in war and peace through active participation in public events and education through outreach programs, public access, and historic demonstration.[217] Her crew of 60 officers and enlisted participate in ceremonies, educational programs, and special events while keeping the ship open to visitors year-round and providing free tours. The crewmen are all active-duty members of the U.S. Navy, and the assignment is considered to be special duty. Constitution is the oldest commissioned warship afloat in the world.[218][Note 1]

The Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston is responsible for planning and performing her maintenance, repair, and restoration, keeping her as close to her 1812 configuration as possible. The detachment estimates that approximately 10–15 percent of the timber in Constitution contains original material installed during her initial construction period in the years 1795–1797.[219]

Constitution is berthed at Pier One of the former Charlestown Navy Yard, at one end of Boston's Freedom Trail. She is open to the public year round. The privately run USS Constitution Museum is nearby, located in a restored shipyard building at the foot of Pier Two.[220] Constitution typically makes one "turnaround cruise" each year during which she is towed out into Boston Harbor to perform underway demonstrations, including a gun drill, and then returned to her dock, where she is berthed in the opposite direction to ensure that she weathers evenly.[221] The "turnaround cruise" is open to the general public based on a "lottery draw" of interested persons each year.[222]

In 2003 the special effects crew from the production of Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World spent several days using Constitution as a computer model for the fictional French frigate Acheron, using stem-to-stern digital image scans of "Old Ironsides."[223] Lieutenant Commander John Scivier of the Royal Navy, commanding officer of HMS Victory, paid a visit to Constitution in November 2007, touring the local facilities with Commander William A. Bullard III. They discussed arranging an exchange program between the two ships.[224]

Constitution emerged from a three-year repair period in November 2010. During this time the entire spar deck was stripped down to the support beams, and the decking overhead was replaced to restore its original curvature, allowing water to drain overboard and not remain standing on the deck.[225] In addition to decking repairs, 50 hull planks and the main hatch were repaired or replaced. The restoration continued the focus toward keeping her appearance of 1812 by replacing her upper sides so that she now resembles what she looked like after her triumph over “Guerriere”号1806 (6), when she gained her nickname "Old Ironsides".[225] The crew of the Constitution and her commanding officer, Commander Matt Bonner, during the bicentennial observances of the War of 1812, sailed Constitution under her own power on 19 August 2012, the anniversary of her defeat of the Guerriere.[226] Bonner is Constitution's 72nd commanding officer.[227]

Notes

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 “Victory”号 is the oldest commissioned vessel by three decades; however, Victory has been in dry dock since 1922.[6]

- ^ Toll explains in detail that Revere did not begin producing sheet copper in the United States until 1801 with the opening of the Revere Copper Company. Sheathing made by Revere was installed during a refit in 1803.[20]

- ^ Cooper, Hollis and Jennings attribute this encounter to the command of Silas Talbot some months later. However, Jennings uses Cooper as a reference and Martin presents a clear argument for attribution to Nicholson.

- ^ "Blow on your matches" was the term for the gun crews to blow on their slow matches to make them white hot for igniting a cannon. The modern day equivalent might be "Prepare to fire".

- ^ The words painted on the sail were in reference to the Little Belt Affair, when “President”号1800 (6) had fired on HMS Little Belt the year prior. Captain John Rodgers of President had mistakenly identified Little Belt as Guerriere. Captain James Dacres of Guerriere had earlier written a challenge of combat to Captain John Rodgers of President.[95]

- ^ The Advertiser reported that the Secretary of the Navy had ordered her to be sold or broken up. Martin presents a valid argument and explanation of Navy procedures for aging ships as to why this was not true, and must have been misreported

References

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Constitution. 美国海军军舰辞典. 美国海军部历史与遗产司令部. [8 September 2011].

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 US Navy Fact File – Constitution. United States Navy. 7 July 2009 [8 September 2011].

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Jennings (1966), p. 36.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hollis (1900), p. 39.

- ^ National Register Information System. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2010-07-09.

- ^ HMS Victory Service Life. HMS Victory website. (原始内容存档于28 August 2012).

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 29.

- ^ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 350 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 49–53.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 29–30, 33.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 42–45.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 61.

- ^ USS Constitution. Naval Vessel Register. [8 September 2011].

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Hollis (1900), p. 48.

- ^ Jennings (1966), pp. 10–11.

- ^ Hollis (1900), p. 49.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Toll (2006), p. 176.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 176–177.

- ^ A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Library of Congress. [17 September 2011].

- ^ Launching the New U.S. Navy. National Archives. [17 September 2011].

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 47.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 55–58.

- ^ Reilly, John. Christening, Launching, and Commissioning of U.S. Navy Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 31 May 2001 [17 September 2011].

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 7.

- ^ Jennings (1966), pp. 17–19.

- ^ Reilly, Jr., John C. The Constitution Gun Deck. Naval History & Heritage Command: 1–13. [17 September 2011].

- ^ FAQ – Guns on board USS Constitution. USS Constitution Museum. (原始内容存档于28 August 2012).

- ^ Cannon Misfires At Boston Pier. Chicago Tribune. 2 February 1995.

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 44.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 24–26.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 69–71.

- ^ Martin (1997), p. 33.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 105.

- ^ Colledge and Warlow (2006), p. 306.

- ^ Winfield (2007), p. 213.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 38, 40.

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 60.

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 70.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 184–185.

- ^ A Cutting-Out Expedition, 1800. Naval History & Heritage Command. 25 October 1999 [17 September 2011].

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 66–68.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 63–66.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 88–90.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 228.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 92.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 173.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 137.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 180.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 142.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 183.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 244.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 143–145.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 248, 250.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 167–172.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 264–267.

- ^ Martin (1997), p. 99.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 184–197.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 272–284.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 206–209.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 199.

- ^ Hollis (1900), p. 115.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 250–251.

- ^ Hollis (1900), p. 117.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 300.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 261–262.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 118–120.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 268–269.

- ^ Jennings (1966), p. 168.

- ^ Hollis (1900), p. 120.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 305.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 122–126.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 272–273.

- ^ Hollis (1900), pp. 124–125.

- ^ Martin (1997), pp. 128, 130–131.